I S K O

Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization

Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging

by Heather Dunn and Paul BourcierTable of contents:

1. Introduction

2. History and current status

3. Nomenclature structure

4. Nomenclature cataloging conventions

5. Relationship with other standards

6. Limitations

7. Future of Nomenclature

8. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

ColophonAbstract:

Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging is a bilingual (English/French) structured and controlled list of object terms organized in a classification system to provide a basis for indexing and cataloging collections of human-made objects. This article presents an overview of Nomenclature’s history, characteristics, structure, use, management, development process, limitations, and future. The system includes illustrations and bibliographic references as well as a user guide. It is used in the creation and management of object records in human history collections within museums and other organizations, and it focuses on objects relevant to North American history and culture. First published in 1978, Nomenclature is the most extensively used museum classification and controlled vocabulary for historical and ethnological collections in North America and represents thereby a de facto standard in the field. An online reference version of Nomenclature was made available in 2018 and it will be available under open license in 2020.

1. Introduction

Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging (often called “Nomenclature”) is a structured and controlled list of approximately 15,000 preferred object terms organized in a → classification system to provide a basis for indexing and cataloging collections of human-made objects. It provides a standard for the creation and management of North American historical and cultural artefacts records by museums and other heritage organizations. As this article will point out, Nomenclature is structurally suited to multilingual development and cross-cultural data exchange. Its bilingual framework (English and French) includes illustrations and definitions that clarify the meaning of concepts. Its simple six-level monohierarchical classification structure groups like objects together by their functional context, such as Harvesting Equipment, Funerary Objects, or Medical Instruments. This standardized classification and controlled vocabulary facilitates the ability to search, use, and share museum collections data for research, collection management, exhibition development, and other museum processes and activities. Nomenclature is available within most commercial collections management systems available in North America. It is also provided as a searchable reference at www.nomenclature.info, and it will be released as Linked Open Data in 2020.

Nomenclature is actively maintained by the Nomenclature Task Force (https://aaslh.org/resources/affinity-communities/nomenclature/), an international group of volunteers appointed by the American Association for State and Local History (AASLH, https://aaslh.org/). Initially published in 1978 as a system for classifying “man-made objects” (Chenhall 1978) in history museums and historic sites, it has been continuously improved and expanded thanks to the input of the museum community it serves. As a result of this collaboration, Nomenclature contains concepts appropriate for cataloging a wide range of human history objects, and addresses the needs of heterogeneous, eclectic, and/or pluralistic collections that might include artworks, natural science specimens, and archaeological objects. One of Nomenclature’s distinctive characteristics is its intelligibility and user-friendliness, making it easy for catalogers with minimal training to comprehend and use efficiently. Although Nomenclature does not cover the specific needs of museums with highly specialized collections, it can be used as a flexible framework which can be expanded as required to express distinctions between types of objects.

2. History and current status

In 1974 Robert Chenhall, then with the Strong Museum (now the Strong National Museum of Play), “and a group of history museum professionals began work on a lexicon to address the need for consistency in naming and classifying collection objects as museums moved toward the computerization of their catalog records”. (Bourcier et al. 2015, vii). In 1978 the group published Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging (Chenhall 1978), the first widespread standard for object description in history museums. The classification system was organized primarily by functional context, an important aspect of Nomenclature that will be critically addressed later in this paper. Like the current Nomenclature, it consisted of a controlled vocabulary of terms organized into ten categories with sub-categories. However, there were only three hierarchical levels instead of the six that exist today, and both preferred and non-preferred terms of various levels of specificity were listed alphabetically. An inverted structure for object terms (still available as an option in today’s Nomenclature) was adopted to collocate similar items in a printed alphabetical index. A bibliography was included to provide museums with further resources on specific types of objects.

By 1984, the first edition was out of print, and the decision was made to revise and expand the 1978 version instead of reprinting it. With the assistance of a committee from across North America, the staff at the Strong spearheaded the work on the second edition, published in 1988 and titled Revised Nomenclature (Blackaby et al. 1995). This new edition reflected the reorganization of some of the classifications from the first edition, and it expanded the content to 8,500 preferred terms (10,000 preferred and non-preferred terms in total).

In 1992, the Canadian Parks Service (CPS) selected terms from The Revised Nomenclature to develop its Classification for Historical Collections (Canadian Parks Service 1992). This system featured a subset of 6,500 keywords most relevant to the CPS collections, organized into the ten categories outlined by the Revised Nomenclature. The CPS standard also included terms not found in Revised Nomenclature but pertinent to the collection of the CPS. In 1997, CPS (renamed Parks Canada) updated and re-introduced their classification system in the form of a visual dictionary. The first volume of the Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects (Bernard 1997) covered categories 1-3: Structures, Furnishings and Personal Objects. Other volumes were intended to follow, covering categories 4-10, but the content was never published in book form. Although it contained fewer terms, the Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects was an improvement on the Revised Nomenclature in some ways; not only was it bilingual (English-French), but it included definitions and illustrations for many object terms, as well as an updated bibliography. The content from the Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects (categories 1-3) and the CPS Classification System for Historical Collections (categories 4-10) were made available online in 2005 as a searchable database. The standard was maintained by Parks Canada, and the database and website were developed and hosted by the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN). The electronic files were also made available on demand to Canadian museums and museum studies programs.

Nomenclature became one of the most-used object classification standards in Canada, but the Parks Canada System (besides being used by Parks Canada itself) was more practical for institutions that needed French or bilingual terminology. Some museums whose collections more closely corresponded with the Parks collections found that it met their needs well. A 2016 CHIN survey on collections management practices in Canadian museums (Canadian Heritage Information Network 2016) showed that over three quarters of museum respondents were using either the Nomenclature or Parks Canada classification systems, while 23% were using the Info-Muse classification system for ethnology, history and historical archaeology museums, which is also based on Nomenclature.

In the early 2000s, two decades after the publication of The Revised Nomenclature, AASLH convened a new task force of museum professionals to update its standard, resulting in the publication of Nomenclature 3.0 (Bourcier et al. 2010). A substantial expansion and reorganization of the previous edition, it included 13,700 preferred terms (15,500 terms in total). Terms for new objects (such as digital cameras and modems) or objects that had been overlooked in previous editions (such as Christmas trees and cigarettes) were added, and some terms were relocated or changed. Revised Nomenclature’s hierarchy was expanded with the addition of new sub-classes to make it easier to pinpoint terms within the functional classification. The original, alphabetical lists of object terms within classes and sub-classes were reorganized into three hierarchical levels to accommodate varying degrees of term specificity.

In addition to the new structure and content, new conventions were introduced in Nomenclature 3.0. Each object term was made unique (no homonyms), cross indexing (multiple terms used to describe singular objects) was encouraged for the first time, and non-preferred terms were relegated to the index. An extensive User Guide was included in Nomenclature 3.0 to help Nomenclature users understand the standard and its applications. The fundamental changes introduced in Nomenclature 3.0 were not adopted by the Parks Canada system and the gulf between the two standards widened. Nomenclature 3.0 was published in book format, but was also made available for the first time as an electronic file, available for licensing from the publisher, AltaMira Press. Shortly after Nomenclature 3.0 was published, the Nomenclature Task Force developed an online community hub within AASLH’s website that included a discussion forum (later replaced by blogs), a list of errata, and online forms for Nomenclature users to submit proposals for new terms or changes.

In August 2013, the Nomenclature Task Force began working on an update with AltaMira’s parent and successor company, Rowman & Littlefield. Nomenclature 4.0 (Bourcier et al. 2015) introduced substantial changes to the Water Transportation Equipment class, following a review by maritime field experts. The Exchange Media class and Religious Objects sub-class underwent intensive review as well and many new terms were added. Following consultation with other authoritative lexicons, such as the Getty’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) and the English Heritage Archaeological Objects Thesaurus, numerous terms for archaeological and ethnographic collections were included as well. Terms were added to several classes to accommodate digital objects. Nomenclature 4.0 was released in early 2015 in book form, as an electronic file, and also in e-book format accessible on multiple devices. AASLH updated its website to support users of the new edition.

During the production of Nomenclature 4.0, the Nomenclature Task Force and AASLH were increasingly aware of the challenges of keeping a living, growing standard available in print. Greater numbers of Nomenclature users were seeking to integrate the standard in their collections management systems and online catalogs. The demands of the profession were no longer met by an outdated business model based on printed books. Nomenclature users and the Task Force could clearly see the benefits of moving Nomenclature into a digital format. At the same time Parks Canada had made the decision to discontinue maintenance of their own standard, the Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects. This was unfortunate news for many Canadian museums that relied on the Parks system, particularly those that needed French terminology. By this time, the AASLH Nomenclature Task Force had gained three Canadian members — two from Parks Canada and one from CHIN. The Parks Canada members had served on the editorial committee for the Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects, and CHIN had comprehensive knowledge of existing vocabulary standards, as well as extensive experience with providing online access to heritage resources.

To respond to these challenges, CHIN approached Parks Canada, AASLH and the Nomenclature Task Force and offered to undertake:

- the harmonization of the Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects with Nomenclature 4.0, to retain the strengths of both standards and (re)combine them into a single standard;

- the creation of a complete French version of the new harmonized Nomenclature;

- the creation of a new website to provide free reference access to Nomenclature.

These proposals were accepted and a partnership was formed, with AASLH, Parks Canada, and CHIN providing vocabulary standards and expertise, and CHIN providing technological and financial support, website development, and translation. The publisher of Nomenclature, Rowman & Littlefield, kindly agreed to allow CHIN to create a free online version of Nomenclature for searching and browsing, but not downloading.

CHIN took on the work of harmonizing the standards. Nomenclature 4.0 was used as the “backbone” and Parks Canada terms, illustrations, definitions, codes, etc. were added into the existing Nomenclature 4.0 whenever concepts correlated. CHIN also undertook the creation of a complete French version, with the assistance of a group of highly specialized terminologists within the Translation Bureau of the Government of Canada. All terms, categories, classes, sub-classes, definitions, and notes were provided with a French equivalent. Canadian linguistic or spelling variants were also added where warranted. More than 2,000 bibliographic references were included, combining references from early versions of Nomenclature, the Parks Canada system, and works more recently used by the Nomenclature Task Force. This work of harmonizing the two standards was completed in 2018 and resulted in a single, bilingual, illustrated, comprehensive standard for North American museums cataloging human history collections.

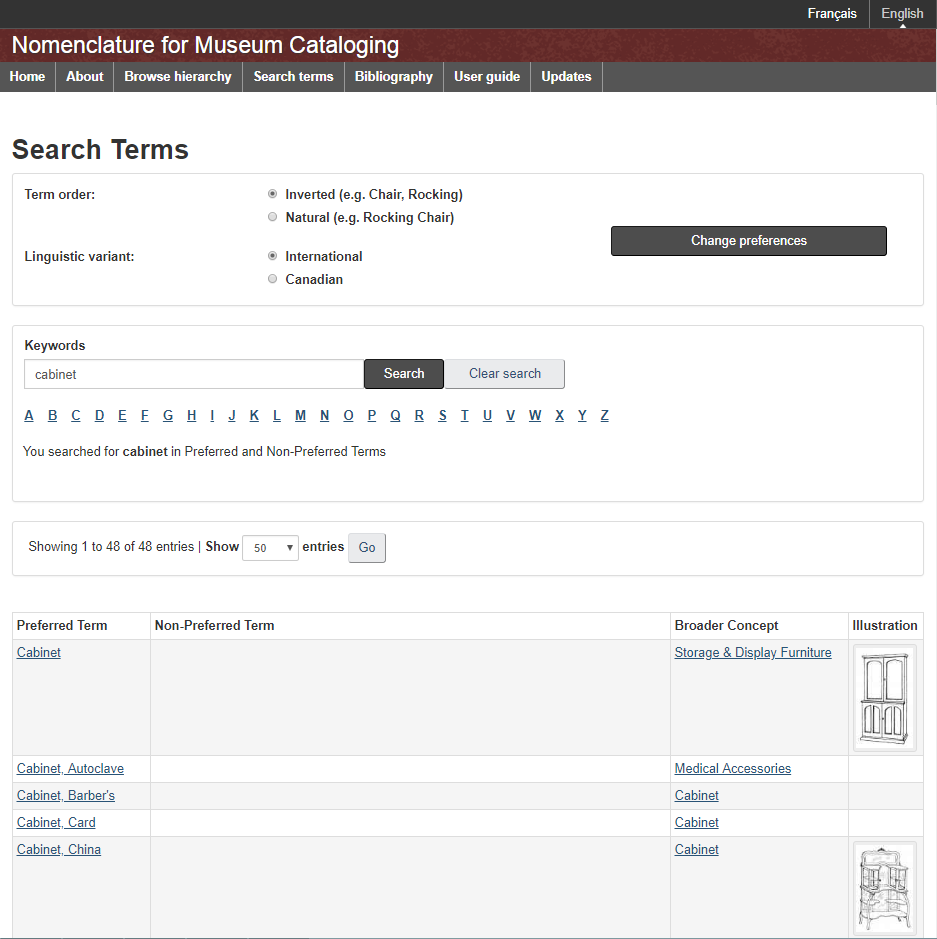

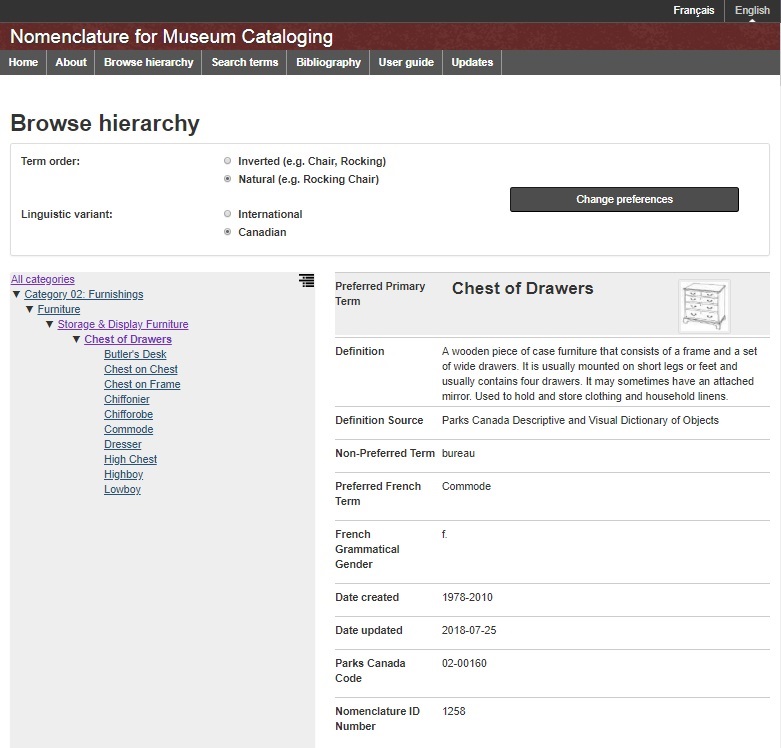

CHIN adopted the PoolParty Semantic Suite for the use of the Nomenclature Task Force editors as it has a number of validation tools and reports that help maintain and develop the terminology. CHIN also developed a public website to allow museums to consult Nomenclature freely. The Nomenclature website (http://www.nomenclature.info/), designed following WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) to ensure that it is as accessible as possible for the visually impaired and for mobile device users, was launched in fall of 2018. It allows users to search for terms (see Figure 1), browse the hierarchy and see term details (Figure 2), and access a user guide and bibliography. The bibliography, which had been excluded from Nomenclature 3.0 and 4.0, is a key addition to the online version. While identifying objects and documenting museum collections, it is helpful to be able to find reference works containing illustrations, definitions, or written documentation on the origin, evolution, and uses of object types. The Nomenclature bibliography contains references that were consulted by the many contributors to Nomenclature. They are categorized following the Nomenclature hierarchical structure in order to help museums find further information on general or specific types of objects.

North American museums have used Nomenclature (and systems based on Nomenclature) for over 40 years. It has long been used in paper-based cataloging systems and integrated with custom-built museum databases, and is available within most commercial collections management systems throughout North America. An internal data analysis conducted by the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) in 2018 found that approximately 70% of Object Type data contributed to Artefacts Canada (the national repository of collections records) by Canadian institutions correlated with the Nomenclature framework. At the time of the study, Nomenclature was not yet fully available in French and did not include Canadian variants so it can be argued that the correlation rate would now be higher. This indicates not only that, throughout Nomenclature’s long history, various museums have consistently used this common standard to accomplish their cataloging tasks, but also that Nomenclature has had a positive impact on data quality, and has thereby improved the ability of museums to collaborate and share information.

Nomenclature has been used to provide online public access to collections for multiple reasons: it has a simple monohierarchical structure that is easy to understand; it covers North American collections extensively; its vocabulary is accessible and lends itself to the improvement of bilingual access to repositories. For example, the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) uses Nomenclature to facilitate bilingual search of online collections records from the Canadian national portal to museum collections, Artefacts Canada.

The most recent version of Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging is its online version, which is updated continuously. Until January 2020, Nomenclature terminology formatted in Excel or RDF files will be available for purchase from Nomenclature’s publisher, Rowman & Littlefield. In January 2020, Nomenclature will be available under open license in multiple formats (tabular and linked data) from the Nomenclature website. These electronic formats are ideal for integration and use within museum collections management systems. Nomenclature will remain available online for browsing and searching as well. Previous versions of Nomenclature are also still available for purchase from Rowman & Littlefield as a paper book or e-publication.

3. Nomenclature structure

Nomenclature assists catalogers in finding the best term to describe an object by grouping like objects together based on their functional contexts. As noted in the introduction to Nomenclature 4.0 (Bourcier et al. 2015, xiv), every human-made object “has discoverable functions, ways in which the object was intended to mediate between people and their environment. There are three ways that objects mediate:

- they shelter us from the environment;

- they act on the environment;

- they comment on the environment”

This is the construct that led to Nomenclature’s overarching categories, namely sheltering (categories 1-3), acting (categories 4-7), and commenting (categories 8-9):

1.Built Environment Objects

2.Furnishings

3.Personal Objects

4.Tools & Equipment for Materials

5.Tools & Equipment for Science & Technology

6.Tools & Equipment for Communication

7.Distribution & Transportation Objects

8.Communication Objects

9.Recreational Objects

10.Unclassifiable Objects

Most categories are divided into functional classes, and many classes are further divided into sub-classes. These top three hierarchical levels (category, class, sub-class) are larger groupings of objects rather than object names, and often appear in the plural form (e.g. Ceremonial Objects or Household Accessories). Indentation is used to display the hierarchical relationship as follows:

- Category

- Class

- Sub-Class

- Class

The next three hierarchical levels (Primary Term, Secondary Term, Tertiary Term) are names of objects and are generally expressed in the singular form (e.g. Chalice, Cathedral, Photograph). Again, indentation is used to show the relationship between broader and narrower terms:

- Primary Term

- Secondary Term

- Tertiary Term

An example of the full classification structure, including all six levels, is as follows:

Furnishings(Category)Furniture(Class)Storage & Display Furniture(Sub-class)Cabinet(Primary Object Term)Cabinet, Kitchen(Secondary Object Term)Cabinet, Hoosier(Tertiary Object Term)

The hierarchical arrangement of object terms within the classification structure helps catalogers determine the most appropriate term for the object they are describing. They can choose a general term or one that is very specific, depending on their knowledge of the object and their requirements for access.

In addition to facilitating the work of catalogers, the hierarchical arrangement of object terms also expedites data retrieval. Object searches can be narrowed or broadened to include, for example:

- all items of furniture, all seating furniture, only chairs or only some particular type of chair

- all musical instruments, all keyboard instruments, only pianos or only spinets

- all sports equipment, all hockey gear, only hockey sticks or only goalie sticks

For categories, classes and sub-classes, the general organizing principle of Nomenclature is functional context, with a dedicated category (unclassifiable objects) for artifacts that do not fit neatly within the confines of explicit object function groupings. Object terms are organized by functional context when possible as well. Functional context differs from function. As an example, a purely functional organizational strategy would group all cutting tools together — scissors, scalpels, razors, kitchen knives, and shingle cutters — regardless of the purposes of cutting. Context provides a more useful framework for intellectual access. Functionality as a conceptual framework has been found to work well because it is adaptable and expandable to various concepts, domains, and cultures. For example, objects such as chopsticks function as a tool, no matter the culture, time period, or geographic origin. This makes Nomenclature a highly useful standard for the meaningful interchange of data.

It is sometimes “impossible or impractical to differentiate on the basis of functional context because the functional context is common to all objects of a specific type, or because objects are used for multiple or unknown functions”. (Bourcier et al. 2015, xv). In these cases other attributes (such as form, location, material, context of use, method of construction, method of operation, method of propulsion, or fuel source) are used to group similar concepts. For example, the Watercraft subclass is primarily arranged by function (e.g. Pleasure Craft or Commercial Fishing Vessel, but where necessary the concepts are sub-divided by other attributes such as method of propulsion (e.g. Sailboat) or fuel source (e.g. Steam Launch). Another example is illustrated by the Art class of Nomenclature, which contains objects that were “originally created for the expression and communication of ideas, values, or attitudes through images, symbols, or abstractions”. These cannot be further sub-divided on the basis of function, so the groupings within the Art class are based on attributes such as medium (e.g. Sculpture).

4. Nomenclature cataloging conventions

The Nomenclature User Guide (available both printed and online) provides guidelines to make recording, searching and sharing collection data easier and more consistent. For example, Nomenclature provides guidelines for:

- cataloging unknown objects

- adding terms to the Nomenclature system (e.g., regional or specialized terms)

- complex cataloging cases (e.g., toys and models; containers and their contents; object components and fragments; object sets) that many museums encounter

Multiple methods of dealing with specific cataloging problems are sometimes suggested, and museums can make choices based on their practical requirements and limitations. Institutions are advised to document their own in-house cataloging conventions so that consistent practices are established and followed.

Nomenclature is a monohierarchical classification system: each unique object term has only one position in the hierarchy and each term has only one immediate broader term (parent term). However, a single object can serve multiple functions or be named with terms that describe its various characteristics. For this reason, catalogers are strongly encouraged to use more than one term to describe a singular object if doing so will improve access. Cross-indexing is one of the most important features of the Nomenclature system and is especially important for:

- objects with more than one function

- objects that comprise various components for which specific object terms exist

- objects that have had different functions over time

- certain documentary objects for which a distinction must be made between the media for recording information, and the recorded information

- digital objects for which a distinction must be made between the physical media for recording digital information, the applications used to create the digital object, and the digital object itself

5. Relationship with other standards

In the years since it was first published in 1978, Nomenclature has been the basis for the development of many complementary and competing standards such as:

- the Parks Canada classification system and the Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects

- the Info-Muse classification System for ethnology, history, and historical archaeology museums

- the Objects Facet of the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT)

The Art & Architecture Thesaurus, maintained by the J. Paul Getty Trust, is closely related to Nomenclature, with many of the terms in its Objects Facet originating from Nomenclature’s second edition. As the AAT has continued to grow and develop, the Nomenclature Task Force has regularly consulted the AAT during the development of Nomenclature terminology. As a result, there is significant overlap between Nomenclature’s content and the Objects Facet of the AAT. Nonetheless, approach, content, and structure differ significantly because the Getty’s conceptual methodology is fundamentally more complex; functional context is just one of many underlying organizing principles in the AAT’s Object Facet. The AAT lexicon has an intricate polyhierarchy and contains a large number of highly specialized concepts that are specific to the art and architecture domains, and institutions, specialists and academics focusing on these fields thus highly value the AAT. While the depth and complexity of the AAT is a strong incentive for art history professionals to use it, it might be a drawback for catalogers in small history museums who desire greater simplicity and relevance to the types of objects they manage, especially certain types of tools and equipment. Nomenclature was developed to meet the needs of history museums and historic sites in North America, many of which rely on staff and volunteers with minimal cataloging training. The simplicity of Nomenclature’s structure, its practical approach to cataloging, its focus on terminology for North American cultural collections, and the relative generality of its terminology are valued by museums facing high staff turnover, low budgets, and limited time allotted to cataloging.

Nomenclature is sometimes used together with other standards for object naming and classification. Because it does not include every term needed by museums, especially those with highly specialized collections, Nomenclature can be used as a flexible framework and supplemented with more specific terminology as needed. For example, a museum with holdings exclusively relating to canoes would likely need to use specialized lexicons to further differentiate the several types of canoe that are already accounted for in Nomenclature. Since Nomenclature has inspired so many complementary specialized frameworks, it is easily compatible and allows institutions to adapt it to their needs. For example, history museums with diverse art collections may supplement the terminology in Nomenclature’s “Art” class with additional specialized terms from AAT.

Nomenclature is used for controlling units of information for the naming and classification of objects, and is not intended to be used for controlling terminology for subjects, materials, cultures, time periods, techniques, locations, personal and corporate names, etc. To control these other units of information, museums use compatible specialized controlled vocabularies, including the Thesaurus for Graphic Materials, Library of Congress Subject Headings, Thesaurus of Geographic Names, Artists in Canada, the Union List of Artist Names, as well as the Materials Facet, Styles and Periods Facet, and Processes and Techniques Hierarchy of the AAT, among many others.

In addition to controlled vocabulary standards such as Nomenclature, museums also use many other types of standards. For example, SPECTRUM (a procedural standard and metadata standard), Cataloging Cultural Objects (a data content standard), and the CIDOC-CRM (a semantic reference model) could be used within a museum information system in combination with several lexicons such as Nomenclature and the AAT. The Nomenclature Task Force continues to develop the Nomenclature standard and routinely uses complementary standards to do so. There will be opportunities for closer collaboration in the future.

6. Limitations

A wide variety of museums have used Nomenclature successfully for many years, but it is not without limitations. Its focus is on historical and ethnological collections, and although it does include a place in the hierarchy and some general terms for artworks, natural science specimens, and archaeological objects, it is not completely sufficient for museums with large and diverse collections of these types. Its focus on terminology for North American objects also means that it may not be sufficient for museums with large collections of object types that originate in other parts of the world. These limitations are extenuated by Nomenclature’s easy extensibility and its compatibility with other complementary standards. The continuing effort to enhance Nomenclature through data exchange with AAT and other standards will also mitigate these limitations.

Some shortcomings in the content of Nomenclature have arisen out of the way that it has evolved. As noted in the “Introduction” to Nomenclature 4.0 (Bourcier et al. 2015, xvi),

The Nomenclature system […] has come about through voluntary contributions of terms and hierarchical structures by those institutions and individual professionals having sufficient interest, inclination, and expertise to make meaningful contributions […]. Predictably, some individuals and institutions have invested more effort and energy than others. Just as predictably, some of the terms suggested for inclusion in the lexicon may represent personal, institutional, or regional preferences that do not reflect as broad a consensus as might be desired. Some areas of the Nomenclature hierarchy contain very specific terminology, whereas others have been developed only to a very general level. As contributions from multiple independent sources are merged, some inconsistencies and even contradictions are apt to be stirred into the mix, despite the best efforts of the Nomenclature Task Force and editors.

As Nomenclature continues to grow and evolve, the Nomenclature Task Force is continually mindful of the need to include enough specificity to meet the needs of the majority of users with general collections while not including so many highly specific or regional terms as to overcomplicate the cataloging process. Occasionally Nomenclature concepts are moved to a different position within the hierarchy or even deleted in order to rectify problems as they are identified, but in general the Task Force attempts to minimize changes to existing concepts.

Nomenclature is only available in English and French at present, and only includes definitions and illustrations for a small percentage of concepts. Availability is also currently somewhat limited: although it can be freely accessed online in a read-only format, users who wish to obtain the Nomenclature data for integration with their systems must purchase a license. These limitations will be rectified when Nomenclature is released as Linked Open Data in 2020, and the data has been enriched through co-referencing with other Linked Data sources.

A monohierarchical classification system is simpler than a polyhierarchical one, and one reason Nomenclature adopted a monohierarchy was a practical limitation of the book format it used until recently; a multihierarchy would necessitate the repetition of many terms within the hierarchy, and that would have added pages (and cost) to the production of a book. Another reason for the monohierarchy is that the lexicon framework of some collections software systems that use Nomenclature do not readily support polyhierarchical relationships. One drawback of a monohierarchical approach is the application of multiple terms in instances that may be counterintuitive. For example, a cataloger would need to name a wedding dress both Dress and Dress, Wedding to cross-index the object as both an article of outerwear and a ceremonial wedding object. However, Nomenclature provides helpful “may also use” instructions for catalogers interested in cross-indexing.

Nomenclature’s primary organizational principle is the functional context of the object. There are other ways of grouping and organizing objects, however. For example, the Social History and Industrial Classification (SHIC) (SHIC Working Group 1983) which is used by many British museums with human history collections, organizes concepts by the interaction between the objects and the people who use them. Major divisions are Community life, Domestic and family life, Personal life, and Working life. Another departure from Nomenclature’s functional approach is illustrated in the recent report, Lexicon Usage and Indigenous Cultural Belongings, by the American Association of Museums (AAM) Collections Stewardship Task Force, which noted that some survey respondents using Nomenclature found it “difficult to incorporate additional terms, including terms supplied by Indigenous communities, since this classification system is organized around use, and not all cultures use objects in the same way”. (AAM 2018, 15). This concern may be mitigated by using the cross-indexing feature of Nomenclature: multiple ways of using an object can be represented by assigning multiple Nomenclature terms to it in order to represent the different ways that the object is used in different cultures. It can be argued that having to contend with objects from various cultures within North America, it was necessary for Nomenclature’s creators to refine the categorization to account for diverse frames of reference and visions of the world. In this sense functional context is uniquely suitable as an organizing principle. However, the Nomenclature Task Force is aware that some adjustments may be necessary in order to incorporate Indigenous concepts, and discussions with representatives of Indigenous communities have been initiated. Such contributions will further strengthen Nomenclature by forcing the NTF to find cross-cultural categories that intrinsically rely on the methodological function of the object rather than only considering its use within the context of a single culture or time period.

An important purpose of a controlled vocabulary like Nomenclature is to promote consistency in preferred terms and to ensure that catalogers assign the same term to similar objects. Catalogers sometimes perceive that the use of a common standardized lexicon diminishes the richness or precision of the data, discouraging the use of regional, ethnic, or specialist terms that their staff and visitors may find more meaningful. But this perceived limitation is actually a strength of controlled vocabularies: regional, ethnic, or highly specialized terminology can be added to the controlled vocabulary as non-preferred or narrower concepts in order to ensure that the standardized information will be broadly understood and easily shared, while the richness of local or specialized terminology is also retained.

As with any classification system, the “Preferred” object names Nomenclature recommends are not preferred across all groups and cultures. Knowledge organization systems have always enabled people to identify and organize concepts in a way that is useful to them, using their own terminology. But semantic web technologies have made it much easier to connect equivalent concepts in different knowledge organization systems. Meaningful data interchange and knowledge sharing is enabled by such technologies and can contribute to overcome barriers such as disagreement on preferred terms, multiple languages, and different ways of organizing and understanding the world.

7. Future of Nomenclature

Nomenclature continues to be developed and maintained by the Nomenclature Task Force (NTF), with updates performed directly within the vocabulary management system and immediately reflected on the public website. Individual or institutional users are welcome to propose additions or changes using the term submission forms found on the Nomenclature Community website (https://aaslh.org/resources/affinity-communities/nomenclature/). The Nomenclature Task Force also strives to collaborate with domain experts to develop and improve Nomenclature and coordinate its efforts with other standards organizations and committees that are responsible for terminology development.

CHIN and Rowman & Littlefield have reached an agreement that will allow CHIN to make Nomenclature available under an Open Data Commons (ODC-by) license as of Jan 1, 2020. CHIN plans to make the data freely available in various formats, including as Linked Open Data (RDF). This will present new opportunities for data enhancement through collaboration and co-referencing with other standards. CHIN and AASLH have already provided the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Vocabulary Program with French terms to be added to the Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). Reciprocally, the Vocabulary Program will assist in co-referencing AAT and Nomenclature concepts in order to enrich Nomenclature’s data with definitions, multilingual terminology, and other valuable information from the AAT. Once Nomenclature is published as Linked Open Data, such data sharing and exchange with other linked data sets will become much easier.

CHIN and the NTF will continue to look for opportunities to improve Nomenclature. In addition to publishing Nomenclature as Linked Open Data, other features (such as visualization options, links to external linked data sources, and bibliography improvements) will be added to the Nomenclature website over time to support greater understanding of the standard and collaboration across institutions. The NTF is also considering the addition of other languages of interest to the museums that use Nomenclature. For example, Spanish terminology and Indigenous North American languages are being considered for addition.

8. Conclusion

Since 1978, Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging has provided North American museums with an easy-to-use standard specifically designed to provide access to their collections of human-made objects. Nomenclature was first developed by and for museums, and over the years it has been continually improved and expanded by inviting input from its users. It is used to standardize museum cataloging, and to enable the search and use of museum collections data for research, collection management, exhibition development, and other museum processes and activities. Now available as an online reference, illustrated and fully bilingual, Nomenclature is more accessible and easy-to-use than ever. It has been incorporated into most North American collections management systems and is also used as a tool to allow easy public access to online museum collections data. Nomenclature will be available under open license in 2020, and users will be able to browse and search Nomenclature, download it, and use it as Linked Open Data. Nomenclature’s simple but expandable classification structure and its focus on controlled vocabulary for objects commonly found in North American historic and cultural collections make it highly valuable to both museums and the public. Nomenclature will continue to grow and develop to meet the needs of the museums that use it.

References

American Association for State and Local History (AASLH). 2018. Nomenclature Affinity Community. American Association for State and Local History (AASLH). 2018. https://aaslh.org/resources/affinity-communities/nomenclature/.

American Association of Museum (AAM) Collections Stewardship Lexicon Task Force. 2018. Words Matter: Lexicon Usage and Indigenous Cultural Belongings. 2018. Lexicon Task Force. Washington, DC: American Alliance of Museums. https://static1.squarespace.com/....

Bernard, Louise. 1997. Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects: Based on the Parks Canada Classification System for Historical Collections. Vol. 1. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Heritage, Parks Canada.

Blackaby, James R., Patricia Greeno, and Robert G. Chenhall. 1995. The Revised Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging: A Revised and Expanded Version of Robert G. Chenall’s System for Classifying Man-Made Objects. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Bourcier, Paul, Heather Dunn, and The Nomenclature Task Force (eds.) 2015. Nomenclature 4.0 for Museum Cataloging: Robert G. Chenhall’s System for Classifying Cultural Objects. 4th ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bourcier, Paul, Ruby Rogers, and the Nomenclature Committee (eds.) 2010. Nomenclature 3.0 for Museum Cataloging: Robert G. Chenhall’s System for Classifying Man-Made Objects. 3rd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN). 2000. Artefacts Canada. 2000. https://app.pch.gc.ca/application/artefacts_hum/indice_index.app?lang=en.

Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN). 2016. Collections Management in Canadian Museums: 2016 Results. 2016. https://www.canada.ca/en/heritage-information-network/services/collections-management-systems/collections-management-museums-survey-results-2016.html.

Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN), American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) Nomenclature Task Force, and Parks Canada. 2018. Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging. 2018. http://www.nomenclature.info.

Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN), and Parks Canada. 2009. Parks Canada Descriptive and Visual Dictionary of Objects. 2009. https://app.pch.gc.ca/application/dvp-pvd/appli/descr-eng.php.

Canadian Parks Service (ed.) 1992. Canadian Parks Service Classification System for Historical Collections. English. Ottawa, ON: National Historic Sites, Parks Service, Environment Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/pc/R61-2-15-1-eng.pdf.

Cataloging Cultural Objects. 2006. English. Chicago, IL: American Library Association (ALA).

Chenhall, Robert G. 1978. Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging: A System for Classifying Man-Made Objects. Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History.

CIDOC Documentation Standards Working Group (DSWG) and CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. 2015. CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (version 6.2). English. CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. Paris, FR: ICOM/CIDOC Documentation Standards Group. http://www.cidoc-crm.org/.

Collections Trust. 2017. Spectrum (version 5.0). English. London, GB: Collections Trust. https://collectionstrust.org.uk/spectrum/.

J. Paul Getty Trust. 2017a. Art & Architecture Thesaurus (version 3.4). English. Getty Vocabularies. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute. http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/.

J. Paul Getty Trust. 2017b. Thesaurus of Geographic Names (version 3.4). English. Getty Vocabularies. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute. http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/tgn/index.html.

J. Paul Getty Trust. 2017c. Union List of Artist Names (version 3.4). English. Getty Vocabularies. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute. http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/index.html.

Museum Documentation Association and Social History and Industrial Classification (SHIC) Working Party (eds.) 1993. Social History and Industrial Classification (SHIC): A Subject Classification for Museum Collections. 2nd ed. Cambridge, GB: Museum Documentation Association.

SHIC Working Group. 1983. Social History and Industrial Classification (SHIC). English. Sheffield, GB: University of Sheffield.

Social History Curators’ Group. 2019. Social History and Industrial Classification (SHIC). 2019. http://www.shcg.org.uk/About-SHIC.

Société des musées du Québec (SMQ). 2012. The Info-Muse Classification System for Ethnology, History and Historical Archaeology Museums (version 3). English, French. Québec, QC: Société des musées du Québec (SMQ). https://www.musees.qc.ca/fr/professionnel/guidesel/doccoll/en/classificationethno/index.htm.

Version 1.0; published 2019-03-07

Article category: KOS, specific (domain specific)

This article (version 1.0) is also published in Knowledge Organization. How to cite it:

Dunn, Heather and Paul Bourcier. 2020. “Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging”. Knowledge Organization 47, no. 2: 183-194. Also available in ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization, eds. Birger Hjørland and Claudio Gnoli, https://www.isko.org/cyclo/nomenclature

©2019 ISKO. All rights reserved.