I S K O

Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization

Subject analysis

by Hanne Albrechtsen(This article is a version of an article published in 1993, see colophon)

Table of contents:

1. Introduction

2. Current methods for subject analysis and indexing

3. What does it mean that a document has a subject?

4. Conceptions of subject analysis

4.1 The simplistic conception of subject analysis

4.2 The content-oriented conception of subject analysis

4.3 The requirements-oriented conception of subject analysis

5. Discussion and conclusion

Endnotes by IEKO editors (2024)

References

ColophonAbstract:

Discusses the nature of subject analysis, suggesting three different conceptions of this: simplistic, content-oriented, and requirement-oriented, considering the type of subject information and indexing method appropriate for each.

1. Introduction

Preparing an index to a book or assigning indexing terms to documents involves the task of subject analysis. Subject analysis can be defined as "the intellectual or automated process by which the → subjects of a document are analyzed for subsequent expression in the form of subject data" (Hjørland 1992a, 40-3, here translated from Danish). Is automatic indexing a challenge, or even a threat to indexers? What do we mean when we talk about "subjects" of books and other documents? Are there different conceptions of subjects, and hence of subject analysis; and if so, are such conceptions interconnected with methods applied for indexing?

These questions are important because discussions of indexing tend to focus on the performance of automated indexing (Korycinski and Newell 1990) versus the performance of human indexing (Jones 1990). Automated indexing is usually based on relevance judgments compiled from particular groups of IR-system users (Cleverdon 1984), or observations of interindexer consistency (Cooper 1969). Using performance as a criterion for finding a "winning" approach to subject analysis and indexing implies a model which restricts itself to comparing the two techniques. Based on empirical observations of user and indexer behaviour, it represents a mechanistic evaluation method for subject assignment and retrieval. This article presents an alternative model for discussing subject analysis and indexing, where the choice between particular methods applied for this task is of minor importance. The intention is to attempt to place indexing in a wider social context beyond such mechanistic evaluation methods and to point towards new challenges for us as indexers.

2. Current methods for subject analysis and indexing

The process of creating subject data, i.e. subject entries for books or descriptors for documents in IR-systems, involves two major steps:

- subject analysis of a → document and expression of the perceived information in a concrete linguistic statement;

- assigning the document with terms elicited in the linguistic statement, where these terms can be translated to conform with the terminology of a controlled vocabulary of indexing terms, for instance according to a → thesaurus or a classification scheme.

This methodology is generally recommended as GIP (good indexing practice) to professional indexers. Examples include the International Standards Organization (ISO 5963:1985), Foskett (1982) and Dutta & Sinha (1984). As pointed out by Frohmann (1990) and by Blair (1990), the majority of the literature on subject indexing concentrates on step two and fails to provide precise rules for realizing step one where the challenge presented is: finding the subject(s) of a document. It should be mentioned, however, that the International Standards Organization recommends that the linguistic statement of subject contents follows a → facetted approach to elicit concepts from a document. This latter method can be fruitful indeed, provided that it involves → facets of a less generic nature than "agent", "instrument", "object of action" etc.; compare for example ISO's general facets with Mutrux and Anderson's article (1983) and Albrechtsen's (1992a) facet scheme for software. I shall return to such alternative approaches later.

3. What does it mean that a document has a subject?

After some years of magic sleep in the research community of library and information science, the concept of "subject" [1] has been awakened again to constitute a central area of study. Admittedly, the concept sometimes sneaked onto the stage for brief performances disguised under the term aboutness, as for example in → domain analysis (Beghtol 1986). It has been argued, that the concept of → aboutness, introduced by Fairthorne and others (Fairthorne 1969) was eventually introduced to avoid the difficulties of addressing the concept of subject proper, and that the previous vagueness of the concept of subject was transferred to the concept "aboutness". With a few exceptions, including Hutchins (1977) and Beghtol (1986) both stressing the issue of intertextuality, the aboutness approaches tended to handle documents as isolated sources of knowledge. At the same time, one may regard in particular Hutchins' work with discourse analysis, involving analysis of text organization [2] as offering an interpretative approach to automatic text analysis, thus intending perhaps to inject a softer, humanistic flavour to what could otherwise be criticized as "hard" automatic indexing approaches, based on statistical and/or computational linguistic techniques, approaches which have dominated research in indexing during the 1970s and 1980s, for example the work of Hutchins (1977), and Salton and McGill (1983).

In contrast to the aboutness approaches, at the same time challenging research in automatic indexing to reconsider their methodological weaknesses, Blair (1990), Hjørland (1992b), Weinberg (1988), and Soergel (1985) point towards new ways of looking at indexing. They reinstate the concept of subject in the leading part for the practice and theory of indexing, stressing that the primary function that indexing should serve is the search for knowledge. They recommend that the indexer should not focus exclusively on the contents of documents, but attempt to anticipate the impact and value of a particular document for potential use [3]. "Indexing fails the researcher", says Weinberg (1988), because the indexes provide the "aboutness" rather than the "aspect", that is the point-of-view or innovation [4] of a document, which cannot readily be perceived by interpreting a document as an isolated source of knowledge. Soergel (1985) and Hjørland (1992b) both advocate that the traditional implicit definition of subjects as direct abstractions of single documents, which is also applied by researchers in automated indexing, as for example in the work of Korycinski and Newell (1990), is too narrow. Soergel proposes a method of request-oriented indexing. Hjørland offers a new definition of the concept of subject as the totality of epistemological potentials of documents.

4. Conceptions of subject analysis

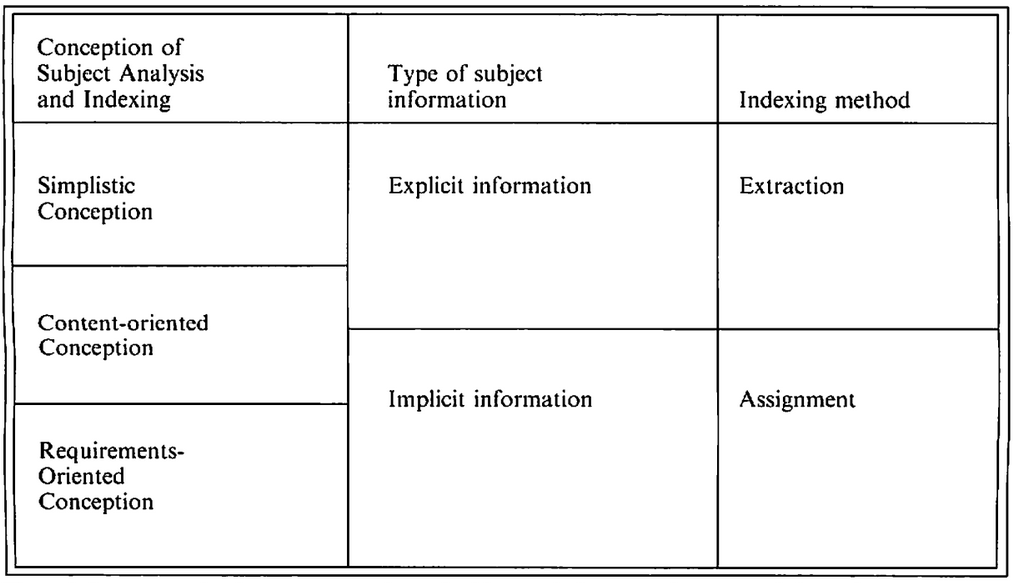

In order to have a clear reference frame for discussing subject analysis and indexing, I stipulate a model of conceptions of subject analysis and indexing. The model, shown in figure 1, covers three different conceptions or viewpoints of subject analysis and indexing.

The simplistic conception (i) regards subjects as absolute objective entities that can be derived as direct linguistic abstractions of documents or summed up like mathematical figures, using statistical indexing methods. According to this conception, indexing can be fully automated.

The content-oriented conception (ii) additionally involves an interpretation of the document contents that goes beyond the lexical and sometimes grammatical surface structure, which is the boundary within which the simplistic conception (i) operates.

Subject analysis of document contents involves identification of topics or subjects that are not [necessarily] explicitly stated in the textual surface structure of a document, but they are readily perceived by a human indexer. Hence it involves a more indirect abstraction of the document itself.

The requirements-oriented conception (iii) regards subject data as instruments for transfer of knowledge, hence aiming at finding pragmatic information or knowledge. According to this conception, documents are created for communicating knowledge, and subject data should hence be tailored to function as instruments for mediating and rendering this knowledge visible to any possible interested persons.

I shall provide some critical comments on each approach, using examples from my work with classification and indexing of software and domain analysis of computing. From 1987 until 1991, I participated in the ESPRIT project PRACTITIONER, whose primary aim was to construct a thesaurus of software engineering terms, derived from automatic analysis of terminology applied in machine-readable software documentation (Albrechtsen 1990). While this approach was fruitful for getting an insight into terminological problems of the domain of software, it failed to facilitate a communication of knowledge about software beyond a narrow technical community. In contrast, domain analysis (Albrechtsen 1992a) regards software as involving both knowledge production and use in a broad societal and interdisciplinary context. Domain analysis entails investigations of scientific, sometimes technical, paradigms and viewpoints which represent different knowledge interests in one domain with the aim of building a classificatory structure to capture knowledge and serve its transfer and sharing. Even though discussions on possible drawbacks of approaches to automatic indexing and thesaurus construction already emerged during the work of the PRACTITIONER project (Sedwell, Kaaber and Albrechtsen 1988), the present model of subject analysis and indexing places itself in the context of this latter domain analysis approach to classification and indexing.

4.1 The simplistic conception of subject analysis

This conception regards subjects as direct abstractions of documents [5]. Following this conception, to analyse and index software is equivalent to extracting automatically all single words or phrases from full-text software documentation.

It is often argued that technical documents like software documentation are amenable to fully automatic indexing approaches, due to a so-called "hard" and unambiguous terminology applied by the document producers. This is not always true. For instance, experiments with automated and human indexing of UNIX online documentation project (Sedwell, Kaaber and Albrechtsen 1988) showed that the human indexers (software engineers) often perceived subjects in this documentation which were not readily stated in the text. One example: the UNIX utility COMM, which can be used for comparing two text files, does not feature the term compare or any of its natural language equivalents in the machine-readable documentation. For automatic indexing of this software, this implies that users searching for utilities that can compare two files will not retrieve this item.

This is not to say that automatic techniques should be rejected as an approach to subject analysis. Rather, this has practical limitations. More seriously, one may contend that it lacks a theoretical foundation for subject analysis other than computational linguistics and statistics.

4.2 The content-oriented conception of subject analysis

The content-oriented conception of subject analysis is based on explicit as well as implicit subject information in texts. By explicit subject information is meant information which is expressed in the terminology applied by the document producer. A document may also convey implicit information, which is not directly expressed by the author, but which is readily understood or interpreted by a (human) reader of the document.

The content-oriented conception of subject indexing is the most common approach to subject indexing, including subject indexing of software (Frakes and Gandel 1990). However, the conception can be said to confine itself to representing or abstracting the document as an isolated entity. Consider for instance Frakes and Gandel's definition of subjects in software:

A software representation is a mapping of predicates and terms describing individual objects and relationships among objects from the represented to the representing world. The representing world may be an elaboration of the represented world, containing new predicates and terms (italics HA).

And similarly, by Hall (1990) in the terminology of Saussure:

[The thesaurus terms] are signifiers and the [software] concept is the signified, with the preferred term acting as a surrogate for the concept ...

Such definitions of subjects in software reveal a content-oriented conception of subject indexing, where the descriptors (representations or signifiers) are predicates for the aboutness or the intentional meaning of a document (Beghtol 1986), hence aiming at achieving an abstraction or a condensed version of software documentation.

The content-oriented conception of subject indexing implies some significant shortcomings, identified by Soergel (1985) and Hjørland (1992b). According to Soergel, the content-oriented conception of subject analysis focuses on the document as an isolated source of knowledge, even though an indexer following this conception may consider the context of the document collection to which it belongs (intertextuality). As a result, the document is assigned to one or more document classes or categories. Hjørland (1992b) argues that a pure content-oriented conception of subject indexing will often result in very trivial descriptors, which cannot be applied to search for more profound aspects like the theoretical reference frame applied, though often not stated in a document. This argument complies with Weinberg's (1988) critique of the aboutness approaches to indexing.

4.3 The requirements-oriented conception of subject analysis

The requirements-oriented conception of subject analysis is applied here as a common denominator for request-oriented approaches (Soergel 1985) and sociological-epistemological frameworks (Hjørland 1992b) for indexing. Subject analysis based on requirements entails a different focus from the content-oriented subject analysis approach. When analyzing a document, the indexer does not concentrate on representing or abstracting the explicit and implicit information in it. Rather, s/he asks: how should I make this document, or this particular part of it, visible to potential users? What terms should I use to convey its knowledge to those interested?

In requirements-oriented indexing it is the users' search for knowledge in IR-systems or indexes to books that determine the method for indexing. Hence, a document is analyzed with the purpose of predicting its potentials for serving particular groups of users. Soergel (1985) advocates that these requirements should also determine the choice of indexing terms, and that the terminology applied by the indexer should comply with the terminology of the users. Soergel's approach places itself within the context of current developments in end-user searching; instead of searching for knowledge in an IR-system, supported by an intermediary, for instance a librarian, the user goes directly to the documents via a user-dedicated search vocabulary. This does not imply the extinction of intermediaries for mediating knowledge. Rather, Soergel's approach represents a change in the division of labour, in particular for the context of IR-systems, where the intermediary functions, traditionally performed by a reference librarian, are handed over to the indexers. However, for indexers of books, this intermediary role has always been a primary responsibility.

In order to achieve an anticipation of user needs, Soergel (1985) proposes a bottom-up compilation of user terminology, for instance for the design of a user-dedicated in-house information system in the industry. This implies that the immediate requirements of a particular user group may be exaggerated at the expense of future users. What will happen when several inhouse databases featuring quite different terminologies and subject indexing approaches are to be integrated in the context of a large company take-over? Apart from such practical, though presumably not unsolvable, situations, one may wonder whether such empirical investigations of user terminology do eventually suffer from the same methodological deficiencies as automatic document indexing. The fact that user-dedicated vocabularies for particular IR-systems can be compiled automatically from logs of end-user search statements points in a mechanistic direction. One should hesitate, on such observations alone, to dismiss empirical investigations of user terminology for building requirements-oriented indexes or IR-systems. For special domains like → fiction, → fine arts and music, empirical investigations of user concepts, using for example association tests, may be a fruitful approach indeed, since these domains involve affective aspects in cognition, which cannot otherwise be captured.

Contrary to Soergel, but following his general idea, Hjørland (1992b) proposes an approach of methodological collectivism for capturing knowledge interests or user needs. He defines subject as "the totality of epistemological interests that one document may serve" [6]. Subjects are viewed as interconnected with scientific and human cognition. For subject analysis and indexing, this view imposes a priority on the indexer to decide on these long-term qualities of a document.

This theory presents a challenge for indexing practice, which I have pursued under the framework of domain analysis of computing. Computing is a crossdisciplinary knowledge domain, which cannot be outlined readily on the basis of conventional criteria for the division of labour, or indeed of the sciences.

Rather, it can be seen as a point of convergence or intersection between different interessees, including the producers as well as the users of computers. Based on methodological investigations of research and technical paradigms in connection with a critical appraisal of current methods for building classification systems and thesauri in this field, I proposed a faceted classification scheme with nine domain-specific facets and experimented with indexing different types of software applications. These facets can be used as a check-tag-list for subject analysis of software. Viewed as a structure, the check-tag-list is an indexing tool, complying with the faceted technique for subject analysis recommended by ISO 5963:1985. Viewed as a framework for capturing concepts and aspects of computing, it constitutes an instrument for transfer of knowledge. In my present work as a teacher of indexing, I am introducing the students to domain and facet analysis of different disciplines in order to train them in building indexing tools which can serve several target groups for indexes. I am also investigating classificatory structures as interaction mechanisms in scientific communication.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Domain-specific approaches to designing indexing tools are open to critique. For instance, Horner (1993) argues that at worst they suffer from the current trend towards fragmentation of knowledge rather than supporting a holistic view. However, my application of domain analysis for indexing aims to facilitate transfer of knowledge in computing between different interessees. The objective is to investigate how domain-specific facets can be generalized between individual knowledge domains. In this context, I will mention a related approach to building indexing tools: the CIFT project, covering the domain of fine arts and literature and featuring aspect-oriented facets such as Scholarly approach and Technique/method. These facets are equivalent to the aspect-oriented facets Scientific Paradigm and Technical approach in my indexing framework for computing.

Domain analysis adheres to the requirements-oriented conception of subject analysis and indexing [7-8], which entails difficulties, when indexing practice enters the stage. Before dismissing the approach on suspicions of impracticality and, even worse, because it may involve the risks of isolating knowledge to an elite of domain experts, as implied in Homers critique, I will summarize the implications of the three different conceptions in the model presented in figure 1.

Subject analysis and indexing can be automated, but fully automated only according to a simplistic conception. The two other conceptions entail far more subjective and, indeed, difficult frameworks and methods for subject analysis. The difficulty lies in part in the fact that the concept of subject still constitutes a pioneering area of study for research and practice in indexing.

All three conceptions have advantages and drawbacks. The advantage of following a simplistic conception is pragmatic: due to the current decrease in the pricing of computers and software, and the increasing cost of manpower, automatic indexing is hard to compete with on an immediate economical basis. The major drawback is that it does not aim at facilitating the transfer of knowledge to possible interessees in the documents it processes. This drawback may eventually render the technique expensive in the long run, if one considers the transfer and optimum use of knowledge as a key societal asset.

The content-oriented conception has the advantage of being an established technique for training and professional work in indexing, but together with the simplistic conception, it suffers from being one-sided, as it focuses on representing individual documents or document collections instead of considering their possible uses.

Finally, the requirements-oriented conception has the advantage that it supports the transfer and dissemination of knowledge. One may argue, however, that a major disadvantage for the practice of indexing is that its ultimate goal may only be realized in Utopia. How much "scientific pre-thinking", following Soergel (1985), can we offer as professional indexers, and how do we train students of indexing to follow such a philosophy? How can indexers distinguish subjects of a high or low priority in a document and ensure its possible visibility in indexes and IR-systems for the future? How much responsibility should be imposed on us for judging or mediating the qualities of a document to potential users?

Instead of letting the answers to such questions blow in the wind, I suggest that indexers reconsider their practice. Current practice in indexing can be said to confine itself to modest, value-free ethics for dissemination of knowledge. Requirements-oriented indexing involves a high degree of subjectivity and responsibility in choosing among the qualities of documents. Current discussions in other professions, such as teaching and medical practice, tend to question prudent ethics of objectivity in mediating their services to their target groups. Rather than refraining from picking up the challenges posed by the social and cultural reality within which we operate, we should face the music, too. New frameworks like requirements-oriented approaches have potentials for supporting a broad and open transfer of knowledge, which is a primary responsibility of our profession. To choose such frameworks means the end of such "threats" to our profession as automatic indexing, but more important, they provide us with a challenge to gain a new consciousness of the impact of our profession for mediating knowledge.

Endnotes by IEKO editors (2024)

Because Albrechtsen's article was written in 1993, we have added the following endnotes in order to reflect developments in the literature since then.

1. There is an important theoretical and philosophical between the expression "a document has a subject", and "a document is attributed a subject". The first corresponds to the document-oriented view of indexing, while the second corresponds to the request-oriented view of indexing.

2. Hutchins (1978, 180) wrote: "My general conclusion is that in most contexts indexers might do better to work with a concept of 'aboutness' which associates the subject of a document not with some 'summary' of its total content but with the 'presupposed knowledge' of its text". By this he seems to mean knowledge that readers need as a starting point to understand what he also describes as the document's "theme", as opposed to how it is developed in the whole text (that is document's "rheme"), which in his view is only relevant for search by specialized readers. (The concepts of theme-rheme and topic-comments have a complex history in linguistics and their meaning varies across different schools in linguistics.) Request-oriented indexing also does not intend to summarize the overall contents of documents, but to make documents findable in relation to the questions they may answer for the users. The important point here is that the concepts of subject and aboutness are both associated with both document-oriented indexing, request-oriented indexing etc., and both views contain the same problems about the objectivity and subjectivity of indexing. Thus, there are no needs for the term aboutness analysis as distinguished from subject analysis.

3. In this sentence, Albrechtsen begins to describe the request-oriented point of view. The best way to understand the difference between the document-oriented point of view and the request-oriented point of view is to consider the Library of Congress (2008, sheet H 180) "20% rule", which states: "Assign headings only for topics that comprise at least 20% of the work". Against this document-oriented principle states the request-oriented principle: assign headings or classification notations for topics in the document that seem important for the users, and/or for topics that seem poorly represented in the library. It is well known that statistical indexing methods prioritizes terms, which are common within a document, but are rare in the collection of documents, and thus, surprisingly, in a certain way come closer to the request-oriented view.

4. Weinberg (1988) suggests that → aboutness (also referred to as → topic or → theme in linguistics) should be complemented by comment (or rheme), that is what a text proposes as its own new argumentation about its topic. Gnoli (2018, 46) discusses how rheme can be expressed in the Integrative Levels Classification. This is not the same as expressing aspect (or viewpoint or perspective) in subject indexing, another interesting possibility later recommended in the León Manifesto (ISKO Italia 2007) and explored e.g. by Kleineberg (2018), although in this passage Albrechtsen seems to conflate the two.

5. What does Albrechtsen means by "direct abstractions"? We suppose "abstraction" means "the act or process of abstracting: the state of being abstracted" (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, November 11, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/abstraction). Such an abstracting process can be made in different ways, and different people tend to make different abstractions of the same document. Albrechtsen's adjective "direct" may mean that the subjectivity of abstracting is being disregarded. This could also be termed naïve indexing (the document is what somebody in an unreflected way believes what the document is about, including what an automated procedure suggests that it is about). It should also be said that there are many kinds of automated techniques for indexing and classification, which are based on different theoretical/philosophical assumptions, all of which cannot be considered based on a "simplistic" understanding of subjects.

6. This quote from Hjørland (1992) is unfortunately not correct. The correct quote is (p. 185): "Subjects in themselves must thus be defined as the epistemological potentials of documents". A given document may have and endless number of potentials, and thus an endless number of subjects, and the indexer chooses among these subjects. Any given subject assignment is therefore a selection of the aspects of a document, which the indexer finds will best serve the users' needs, viewed from the purpose or policy of a library or a database. Therefore this view may also be called "the policy-oriented view" of indexing, cf. → Hjørland 2017, Section 2.4, 59.

7. The concept of subject analysis/aboutness is broader than just about indexing and classifying documents. In a broader sense, it is about labeling things in ways that provide clues to their uses. As defined by Yablo (2014, 1): "Aboutness is the relation that meaningful items bear to whatever it is that they are on or of or that they address or concern". There is a larger philosophical literature on this concept in the philosophical literature, which needs to be considered from the perspective of knowledge organization.

8. A recent review of aboutness/subject analysis (Holley and Joudrey 2021) takes the document-oriented approach without considering the literature about request-oriented indexing (and by implication also missing the dichotomy between document-oriented and content-oriented indexing). The relative comprehensive literature about this (including Albrechtsen 1993) is ignored, as is the discussion in the literature of the theories presented by Holley and Joudrey, such as Patrick Wilson's thought experiments. Holley and Joudrey claim that conceptual analysis is the process of determining the aboutness of information sources, whereas subject analysis comprises two phases: conceptual analysis and translation. The translation process (p. 160) "entails taking an understanding of the aboutness of a resource and converting it to one or more artificial subject languages, such as a classification scheme and/or standardized controlled vocabularies (e.g., a subject heading list or a thesaurus)". Holley and Joudrey's terminology is at odds with how these terms are ordinarily understood. Conceptual analysis is usually understood as analyzing the meaning of concepts (cf. Furner 2004), not with analyzing aboutness or subjects of documents, whereas subject analysis is usually understood as synonym with aboutness analysis. The result of analyzing aboutness or subjects of documents is called subject assignment, and the whole process of subject analysis and subject assignment is called indexing or classification.

References

Albrechtsen. Hanne. 1990. “Software Concepts: Knowledge Organization and the Human Interface”. Advances in Knowledge Organization 1: 48-64.

Albrechtsen, Hanne. 1992a. Domain Analysis for Classification of Software. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Royal School of Librarianship. (MSc Dissertation).

Albrechtsen, Hanne. 1992b. “PRESS: A Thesaurus-based Information System for Software Reuse”. Classification Research for Knowledge Representation and Organization. Eds. Nancy J. Williamson and Michele Hudon. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers, 137-44.

Albrechtsen, Hanne. 2015. “This is Not Domain Analysis”. Knowledge Organization 42, no. 8: 557-561.

Beghtol, Clare. 1986. “Bibliographic Classification Theory and Text Linguistics: Aboutness Analysis, intertextuality and the Cognitive Act of Classifying Documents”. Journal of Documentation 42, no. 2: 84-113. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026788.

Blair. David C. 1990. Language and Representation in Information Retrieval. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

Cleverdon, Cyril W. 1984. “Optimizing Convenient On-Line Access to Bibliographic Databases”. Information Services and Use 4: 37-47.

Cooper, William S. 1969. “Is Interindexer Consistency a Hobgoblin?” American Documentation 20, no. 3: 266-78. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.46302003141.

Dutta. S. and P.K. Sinha. 1984. “Pragmatic Approach to Subject Indexing: A New Concept”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 35, no. 6: 325-331. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630350604.

Fairthorne, Robert A. 1969. “Content Analysis, Specification and Control”. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 4: 73-109.

Foskett, A. C. 1982. The Subject Approach to Information 4th ed. London: Clive Bingley.

Frakes, William B. and Paul B. Gandel. 1990. “Representing Reusable Software”. Information and Software Technology 32, no. 10: 653-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0950-5849(90)90098-C.

Frohmann, Bernd. 1990. ”Rules of Indexing: A Critique of Mentalism in Information Retrieval Theory”. Journal of Documentation 46, no. 2: 81-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026855.

Furner, Jonathan. 2004. “Conceptual Analysis: A Method for Understanding Information as Evidence, and Evidence as Information”. Archival Science 4, no. 3-4: 233–265. DOI 10.1007/s10502-005-2594-8.

Gnoli, Claudio. 2018. "Classifying Phenomena, part 4: Themes and Rhemes". Knowledge Organization 45, no. 1: 43-53.

Hall, P. 1990. Domain Modelling and Concept Storage. Uxbridge: Brunei University (ESPRIT PRACTITIONER project report, BrU-lS-WP4.1-096).

Hjørland, Birger. 1992a. Informationsvidenskabelige grundbegreber [Fundamental Concepts in Information Science]. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Royal School of Library and Information Science. [In Danish; an English edition co-authored by Hanne Albrechtsen was planned in 1993 but never completed].

Hjørland, Birger. 1992b. “The Concept of 'Subject' in Information Science”. Journal of Documentation 48, no. 2: 172-200. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026895.

Hjørland, Birger. 2017. “Subject (of documents)”. Knowledge Organization 44, no. 1: 55-64. Also available in ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization, eds. Birger Hjørland and Claudio Gnoli, https://www.isko.org/cyclo/subject.

Holley, Ralph M. and Daniel N. Joudrey. 2021. “Aboutness and Conceptual Analysis: A Review”. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 59, nos. 2-3: 159-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2020.1856992.

Horner, David Sanford. 1993. “Paradigms, Discourses and Language Games: Categorical Frameworks and Signs of the Times”. Presentation invited for expert panel on Domain Analysis in Information Science. Summary in ASIS '93. Proceedings of the 56th ASIS Annual Meeting. Columbus (OH) 22-28 October 1993.Medford, NJ: Learned Information, 291.

Hutchins. W. John. 1977. “On the Problem of ‘Aboutness’ in Document Analysis”. Journal of Informatics 1, no. 1: 17-35. (Editors note 2024: probably unavailable, but see Hutchins 1978).

Hutchins, W. John. 1978. “The Concept of ‘Aboutness’ in Subject Indexing”. Aslib Proceedings 30: 172-181.

ISKO Italia. 2007. “The León Manifesto”. http://www.iskoi.org/ilc/leon.php. Also Knowledge Organization 34, no. 1: 6-8.

ISO 5963:1985. International Standards Organization. Documentation. Methods for Examining Documents, Determining Their Subjects, and Selecting Indexing Terms. Genève: International Organization for Standardization.

Jones, Kevin P. 1990. “Natural-Language Processing and Automatic Indexing: A Reply”. The Indexer 17, no. 2: 114-115. https://doi.org/10.3828/indexer.1990.17.2.8.

Kleineberg, Michael. 2014. “Reconstructionism: A comparative method for viewpoint analysis and indexing using the example of Kohlberg's moral stages”. In Fernanda Ribeiro and Maria Elisa Cerveira (eds.). 2018. Challenges and Opportunities for Knowledge Organization in the Digital Age: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International ISKO Conference, 9-11 July 2018 Porto, Portugal. Advances in knowledge organization, 16. Baden-Baden: Ergon, pp. 400-408.

Korycinski, C. and Alan F. Newell. 1990. “Natural-Language Processing and Automatic Indexing”. The Indexer 17, no. 1: 21-29. https://doi.org/10.3828/indexer.1990.17.1.8.

Library of Congress. 2008. The Subject Headings Manual. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Policy and Standards Division.

Mutrux, Robin and James D. Anderson. 1983 “Contextual Indexing and Faceted Taxonomic Access System”. Drexel Library Quarterly 19, no. 3: 91-111.

Salton, Gerard and Michael J. McGill 1983. Introduction to Modern Information Retrieval. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sedwell, Ian, Ulla Kaaber and Hanne Albrechtsen. 1988. The Linguistic Analysis of Unix On-Line Documentation, Unrestricted, P1094-BrU-WPC4-Working Paper-8814 (Technical Report). [Editors comment 2024: This reference is mentioned here: https://www.corneliaboldyreff.co.uk/professional-career/past-research-projects/practitioner-project-p1094. However, we have not been able to further verify or obtain this report, which is also referred to by Albrechtsen 2015].

Soergel, Dagobert. 1985. Organizing Information: Principles of Database and Retrieval Systems. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Weinberg, Bella Hass. 1988. “Why Indexing Fails the Researcher”. The Indexer 16, no. 1: 3-6. https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/epdf/10.3828/indexer.1988.16.1.2.

Yablo, Stephen. 2014. Aboutness. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Version 1.0 published 2024-11-11

Version 1.1 published 2024-11-20: endnotes 2 and 8 added

Article category: Knowledge organizing processes (KOP)

This article is a republished version of:

Albrechtsen, Hanne. 1993. “Subject Analysis and Indexing: From Automated Indexing to Domain Analysis”. The Indexer 18, no. 4: 219-224. Available open access at https://doi.org/10.3828/indexer.1993.18.4.3

Here reproduced with permission from Liverpool University Press.