I S K O

Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization

Bliss Bibliographic Classification second edition (BC2)

by Vanda BroughtonTable of contents:

1. Introduction

2. History of the scheme

2.1 The revision programme

2.2 Radical nature of the revision

2.3 The role of the Classification Research Group

3. Format and scale

4. Published volumes

5. Maintenance of the classification

6. Principles underlying the classification

6.1 Relationship with the first edition

6.2 Main class order

6.3 Modification of main class order: classes, disciplines, and phenomena

7. Structure of BC2

7.1 Facet analysis in BC2: 7.1.1 Fundamental categories; 7.1.2 Facets proper; 7.1.3 Order of classes within facets; 7.1.4 Relationships within facets; 7.1.5 Arrays; 7.1.6 Relationships between facets: combination of concepts

7.2 Citation order: 7.2.1 Citation order between facets; 7.2.2 Citation order between arrays;

7.3 Filing order: 7.3.1 Filing order of facets

7.4 Notation: 7.4.1 Retroactive notation; 7.4.2 Intercalators; 7.4.3 Notational replication and specifiers

7.5 Pre-combination within the schedules

7.6 The alphabetical index

8. Reception of the scheme

9. Influences and collaborations

10. BC2 as a source for a thesaurus

11. BC2 and ontology engineering

12. Users

13. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Endnotes

Published schedules

References

ColophonAbstract:

The paper describes the Second Edition of Bliss’s Bibliographic Classification (BC2), its major features, and the principles on which it is constructed. The historical context of the Second Edition is examined, as is its relationship to the original scheme, and the radical nature of the revision process. Factors which influenced the process of revision are considered, particularly the role of the Classification Research Group, and the emergence of facet analysis as a means of modelling classification schemes. The ways in which BC2 has itself influenced other knowledge organization systems are also discussed. The effects of changing patterns of cataloguing and classification practice in the United Kingdom are shown in relation to the adoption and use of BC2, and some examples are provided of strategies to promote the use of the scheme to a wider environment.

1. Introduction

The Bliss Bibliographic Classification, Second Edition (BC2), is the radically revised and expanded version of → Henry Evelyn Bliss’s original Bibliographic Classification (BC1) published between 1940 and 1953. The Second edition, which began publication in 1977, maintains the general structure and order of BC1, but validates that structure through the use of → facet analysis to determine the detailed internal composition of individual disciplinary classes. The revision has been a radical one in the expectation that it would render BC2 usable in the medium term. In the process of revision much use has been made of the experience of users of BC1, and of the work of the Classification Research Group, several of whose members have been significant contributors.

The classification has been adopted by a modest number of special and academic libraries in the United Kingdom, and it also serves as an exemplar of a faceted → knowledge organization system, and a free-to-access source of terminology in a variety of disciplines. Alongside the → Colon Classification (Ranganathan 1960), BC2 is one of only two widely known faceted general classification schemes in existence and it faces many of the same challenges.

Part of the purpose of the current paper is to document the story of the Second edition, and to create a good account for the historical record (particularly for the use of the Bliss Classification Association), bearing in mind that much of the history of the revision is contained in minor publications or unpublished material (or in personal recollection) none of which are reliably accessible sources in the long term.

2. History of the scheme

The Bibliographic Classification (BC1) of Henry Evelyn Bliss (Bliss 1940/53) was the last of the traditional general → library classifications to appear and was hailed by many as the best constructed and most scholarly of them all, “the fine flower of the enumerative period” (Langridge 1973, 93). Despite that label, it contained many facilities and devices for synthetic classification, what Bliss called “composite specification” or “composite classification” (Bliss 1929, 154-5; Bliss 1940/53, vol. 1, 19), that is the representation of complex → subject content of documents by the building of compound classmarks. In that respect BC1 stands as a bridge between the enumerative schemes of the Nineteenth century, and the fully faceted schemes of the later Twentieth century. BC1 was adopted by many academic and special libraries, particularly in the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth, although it was not implemented in any institutions in the United States, other than Bliss’s own library at the City College, New York, where it had originally been developed and tested, and the Claremont Theological Seminary (Thomas 1998, 81).

In 1955, only two years after the publication of the final volume of the Bibliographic Classification, Bliss died, and continued maintenance of the scheme appeared to be a serious problem. Bliss’s death, however, was the prelude to some significant changes in the management and editorship of BC1, and the British Bliss Classification Association, which had been very active in promoting the classification, now took on the major responsibility for the scheme. Initially, this involved the production of the annual Bulletin of the Bliss Classification Association, which had been started in 1954 under Bliss’s editorship, and which published general news about the Classification, together with additions and amendments to the schedules. Dr. John Campbell assumed the role of editor, but during that time the H. W. Wilson Company remained as the Bulletin’s publisher, and they retained the copyright in the scheme.

The 1966 issue of the Bliss Classification Bulletin was, however, the last to be published by H. W. Wilson, and in the same year BC1 went out of print. The 1966 Bulletin (2) recorded that “the Company feels that their responsibility towards the BC may justly be transferred entirely to the British Committee, both as to the production of the Bulletin, and of a future new edition of the BC”. H. W. Wilson generously transferred the copyright to the British Committee, who acknowledged that Wilson had published the classification “in a spirit of duty to the library profession and in doing so sustained a considerable financial loss” (Mills 1966, 2). In 1967, at the annual general meeting (AGM) of the British Committee a new organization was formed, the Bliss Classification Association (BCA), under the chairmanship of Jack Mills, reader at the then North Western Polytechnic, (later Polytechnic of North London, PNL) School of Librarianship.

2.1 The revision programme

The possibility of a second edition of the Bibliographic Classification had been raised as early as 1954, by Bliss himself writing in the Bulletin (1954, 2-3): “when, after several years, a sufficient accumulation [i.e., of amendments] is on hand, a complete new edition, we hope, may be convenient and economical”. After the formation of the BCA the decision was quickly made to proceed with this new edition, and an appeal was made to the membership of the BCA in 1967, and again in 1969, to create a fund to support the work. This resource was to be supplemented by the Polytechnic in the form of a paid research assistantship, which enabled the drawing up of a programme of work.

Most of the planned work was carried out by the editor-in-chief Jack Mills and his assistants, but was contributed to by colleagues at the School of Librarianship, and, on a pro bono basis, by members of the Bliss Classification Association, users of BC1, and others interested in classification more generally, notably members of the United Kingdom Classification Research Group. Academic subject specialists were also invited to comment on matters such as optimum linear order, expected collocations of topics, and citation order. Many people gave advice on the general structure of subjects, read draft schedules, and provided feedback, and the Bulletin for 1969 (2) records that “a number of classes, some of them extensive ones, have already had, or are having, a great deal of work done on them by individual libraries”. Libraries that had made their own additions or modifications were encouraged to send copies of these to the Polytechnic, and in 1983 a general invitation for participation was published in the academic press (Mills 1983). Some individuals made a more significant contribution in terms of their input, drawing up whole subject classes; particular names include Ken Bell, lecturer at PNL (Philosophy), → Douglas Foskett, librarian at the Institute of Education and later at the University of London Library, with Joy Foskett (Education), Colin Ball (The Arts), and Chris Preddle, sometime secretary of the BCA and librarian at Dr. Barnardo’s (Social Welfare).

Most of the in-house work in collecting and analysing terminology, consulting external sources, and drafting preliminary schedules, was the responsibility of research staff at PNL specifically appointed to the revision project. Staff also had the task of publicising the project and some short journal articles describing the new scheme appeared (Broughton 1974; Mills 1970; 1976b). The original research assistant appointed in 1969 was Valerie Lang, a graduate of the School of Librarianship at University College London, who had previously worked with Kenneth Vernon on the London Classification of Business Studies (Vernon and Lang 1970), but who left in 1972 to take up a permanent library position. She was replaced by Vanda Broughton, another UCL graduate, initially awarded a three year Research Fellowship, but who continued in post until 1990 supported by various research grants from bodies including the Department of Health and Social Services, the King’s Fund Centre, the British Library, the British National Bibliography, and the John C. Cohen Foundation.

2.2 Radical nature of the revision

In addition to the numerous small-scale revisions and additions which Bliss had doubtless imagined would form the basis of the second edition, from 1963 onwards the Bulletin had carried more substantial new schedules for subjects as diverse as electronics (BCB 1964, 10-12), nuclear reactor engineering (BCB 1965, 6-9), sound reproduction and recording (BCB 1965, 10-11), astronautics (BCB 1965, 12-14), food preservation (BCB 1966, 4), gardening and fruit growing (BCB 1966, 9-11), and printing (BCB 1967, 13-16). These were to be the last “new” schedules published in the Bulletin, following a decision recorded in the Foreword to the 1969 issue to focus on the second edition [1]. They were rather different in nature to the earlier material and incorporated much of the theory that had developed in the 1950s and 1960s, firstly following the ideas on faceted classification of → S. R. Ranganathan, and then the particular version of faceted classification which emerged from the Classification Research Group. The Introduction to BC2 (Mills and Broughton 1977, 11 Section 2.41) makes explicit the difference from what has gone before:

Conceptually, they [the new schedules] were completely consistent with the theories of bibliographic classification advanced by Bliss, but may be said to have introduced a more rigorous analysis and a more consistent pattern than the original BC sometimes showed.

This emphasis on revising the internal order and structure of schedules in BC1, in addition to expanding and updating the vocabulary, clearly had some implications for the direction which the revision would take, and the consequent relationship between BC1 and BC2. A major decision to be made therefore was the extent to which the revision should be a radical one.

Curwen’s paper on revision policies in classification schemes identifies some of the criteria involved in establishing the degree of revision which is either necessary or acceptable from the users’ point of view, and examines the approach taken by several schemes including BC2. He summarizes the practising librarian’s point of view neatly when he says (Curwen 1978, 20):

there is a conflict between the static nature of the collection and the dynamic nature of the new acquisitions which may not fit into the established pattern. Librarians want their collections to be up to date and the classification schemes which organize and display those collections correspondingly so, but at the same time they do not want to have to alter the work which has already been done.

As a consequence, all of the bibliographic schemes have been criticised for changes made to their schedules. Curwen identifies the key problems for revisers as being vocabulary and structure, the first to be accommodated without unnecessarily disturbing the second. The complexity of subject content in modern literature challenges both, and in the case of BC2, because of the introduction of facet principles to drive the structure, it was unlikely the disturbance to the order would be minimal.

A memorandum was prepared for consideration by the BCA, which was also published in the Bulletin for 1969, and reproduced in the Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules in 1977. It lays out the argument for making the revision a radical one, considering two major aspects of the work: firstly, the need to update and expand the vocabulary; and secondly, the need to improve structure and consistency. Given that BC1 met many of the desirable criteria for a modern classification scheme, the memorandum lists the following seven factors to be borne in mind (order follows that in the Introduction (Mills and Broughton 1977, 12):

- BC will have gone some 20 years without a comprehensive revision.

- We cannot expect BC to be revised as frequently as DC or LC. So this one must look correspondingly further ahead.

- If a library has to reclassify a given class to any degree it is often the case that a complete revision would not take significantly longer.

- A radical revision of the kind being prepared will produce a far more enduringly satisfying scheme than a piecemeal, patching-up operation.

- Moreover, a revised scheme with a clear facet structure in each class and clear rules for consistent classifying is far easier to maintain and revise than an enumerated one not enjoying these features.

- We assume that present users of BC already use a wide variety of the alternatives offered by the scheme as well as amendments and expansions of their own. As a result, whatever form the revision takes it will inevitably involve many users in varying degrees of reclassification. So we might as well make the best possible job of it.

- A number of positive steps will be taken to minimise the work involved in reclassification. The scope and definition of classes will be indicated with maximum clarity and the crucial problem of compound classes will be met by clear and explicit rules for practical classification.

Generally speaking, these were practical considerations, aimed at ensuring an up-to-date vocabulary and order of classes that would be sustainable in the medium term without further major changes, balanced against the least possible disturbance to existing users. It is noteworthy that some of these factors relate to the extent of the re-classification that would accompany different degrees of revision. Without the benefit of hindsight, it was not anticipated that operating conditions in libraries would change significantly over time, and that in-house classification and re-classification would be in a state of decline in the Twenty-first century. The consequent rise of the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) as the dominant systems in recent times ensured that for most libraries re-classification to LCC or DDC would be an easier and more cost-effective undertaking than re-classification to a radically revised BC, whatever its functional or theoretical merits.

2.3 The role of the Classification Research Group

A particularly powerful influence on BC2 lay in the opportunity which the revision project provided to create a “new” general classification scheme, one which was less US-centric in its approach, and a potential vehicle for recently developed thinking on classification. Such thinking was primarily driven by the faceted classification methods of S. R. Ranganathan which had been the main focus of the Classification Research Group’s work in the preceding twenty years, and which had evolved into a distinctly British version. The role which the CRG played in the creation of BC2 cannot be underestimated. In 1955 they had published in the Library Association Record what is commonly referred to as the CRG “manifesto”, a long statement entitled “The need for faceted classification as the basis for all methods of information retrieval”, and BC2 was to become a test bed for that mission. The CRG’s early expectation had been that the eventual outcome of their deliberations would be a new general scheme of classification, and a number of publications documented that objective (Austin 1969; Classification Research Group 1964a; 1964b; Foskett 1970). Work towards this new general scheme was in part funded by a grant from NATO (Gnoli et al. 2024, 326), an element of the more general effort to improve scientific indexing and dissemination initiated by the Royal Society Scientific Information Conference of 1948, which itself had led to setting up of the CRG. This expectation was thwarted when the work carried out under the NATO funding failed to materialise as a classification scheme, although it resulted in the creation of the → PRECIS indexing system for the British National Bibliography under the direction of Derek Austin, CRG member, and the original research lead for the NATO grant (Austin 1969; 1984).

With the advent of the Bibliographic Classification revision project, the CRG members were naturally interested in this new opportunity for the implementation of their research, and their role in the development of BC2 is openly acknowledged in the Introduction (Mills and Broughton 1977, vi):

Of inestimable value too have been the theoretical and practical contributions of our friends and colleagues in the Classification Research Group which since 1952 has played a significant part in developing the ideas of Ranganathan into the versatile and supple instrument which has made the new BC possible.

Drafts of schedules and discussion papers relating to the BC2 revision were regularly the topic for discussion at CRG meetings from the 1970s onward. Alongside those individuals already mentioned, contributors to the conversation also included Jean Aitchison, → Eric Coates, Robert Fairthorne, Jason Farradane, Barbara Kyle, Derek Langridge and Leonard Will. CRG members who edited or co-edited a volume of the scheme were Eric Coates (Chemistry), and Douglas Foskett, who was instrumental in preparing the second edition of Class J, as well as producing a further revision of that class in 1990 (Foskett 1989). Foskett (1991) also discussed the role played by BC2 in providing a model for a new general classification, using examples of the scheme’s structural analysis.

3. Format and scale

The Association’s original intention was to present the new edition as a two-volume work, similar in scale and detail to BC1. This was to contain an introduction to the scheme, and an alphabetical index, created by chain indexing procedure. Correspondence with the publisher Butterworths in October 1971 reveals that this had been amended to a three-volume work, in crown octavo format. The new schedules were to be typed at the School of Librarianship, using an IBM golf-ball typewriter which allowed for the easy use of a variety of fonts and styles, in a two column format for the schedules, and three columns for the index. This “camera-ready copy” would be delivered to the publisher who would photographically reduce it to create the published version.

The scale of the work was not originally intended to exceed that of Dewey in terms of the number of classes, and it was stated that it could not rival UDC, whose Master Reference File now contains about 65,000 classes. Nevertheless, the Bliss Classification Bulletin for 1969 (Mills 1969, 7), outlining the general principles and policies for revision states that “we assume that the new BC should at least equal, and frequently exceed, the detail provided by DC and LC”. To this end the cumulations of the British National Bibliography were intended to supply the necessary literary warrant, both in the required level of detail, and the identification of new topics. Despite these early intentions, the size of the vocabulary in published volumes has tended to rise over time, and it is likely that the number of classes now far exceeds that of UDC. By the 1990s Thomas (1995, 108) noted that “the degree of specificity of simple terms exceeds that of the Dewey Decimal Classification and is usually greater than that within the Library of Congress Classification”, but that “the high level of detail in BC2 has varied somewhat from published class to class”. As a rough guide, the average number of classes per page on the most recently published volumes for Fine Arts and Chemistry comes in at 54 and 64 respectively, giving an approximate overall total of 7,500 and 6,400 classes for these two disciplines. Although these are both large fields, and the scale is not likely to be replicated across all 27 proposed volumes, a figure of between 100,000 and 150,000 classes (very much in excess of UDC) does not seem untenable.

It had been rather optimistically stated in the 1969 Bulletin that the work would be completed in three years, and a contract with Butterworths publishers was signed in 1972 for delivery by the end of October 1973. It soon became apparent that this could not be achieved, and the 1973 Bulletin (2) records that the Committee intended to deliver the finished schedules by September 30, 1974, which Butterworths had agreed to, “being realistic about the time needed for a large work of this sort”.

As a consequence of further delays, in 1974 it was proposed that the classification be published in parts in order that the schedules for at least some subjects could be made available more quickly. The 1974 Bulletin (2) records that “Mr Mills thought that ideally one should not issue parts before the whole work, as revision of one class often affected others. But he thought publication in parts a workable idea” [2]. At this stage it was envisaged that there would be a separate introductory volume, plus a volume covering the whole scheme in an abridged version. The membership of the BCA was overall in favour of the plan, and the contract with Butterworths was renegotiated. By the time of the Association’s AGM in November 1974, two classes, J Education and P Religion, were considered ready to go to the publisher, but were not then delivered until August 1976, together with the Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules, followed by class Q Social Welfare in December of that year. All four were published in 1977, in the format which had been finally decided on, and which was to remain in place for subsequent print volumes. In these slimmer volumes the crown octavo format was abandoned in favour of A4, the camera-ready copy initially supplied as A3 sheets, to be photographically reduced by the publisher, and for later volumes as PDFs. In practice, the published text was printed onto a larger page size (22x28 cm for the original Butterworths volumes with slight variations of 21.5x27.6 cm and 21.5x28.5 cm from the European publishing houses). In 2002, BC2’s publishers Bowker-Saur discontinued their print operation, and responsibility for the classification was passed to K. G. Saur in Munich (Bliss Classification Association 2002, 3), and subsequently to de Gruyter.

From 1981 onwards production of the camera-ready copy was mechanised, beginning in 1981 with the computerisation of the A/Z index to class H, the schedules for which were still produced manually on the IBM machine. Subsequently, a set of programmes was created to generate the camera ready copy of the schedules from a coded version, but from the early 2000s these were proving unusable to the point that “it had become impossible to produce further copy to send to the publishers” (Curwen 2002, 2), so a new software package was commissioned from Paul Coates which remains in use. Completed schedules maintained as text files are encoded using a form of mark-up to indicate, for example, the position in the linear sequence, and hierarchical status of individual classes, as well as other structural characteristics. This source code is used to automatically generate the camera-ready copy of schedules (which had previously needed to be typed), and the alphabetical index, the latter still requiring some degree of manual editing.

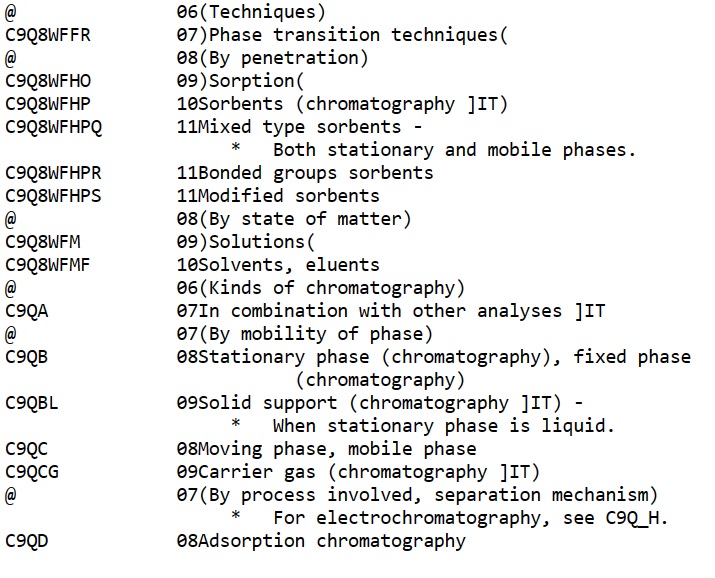

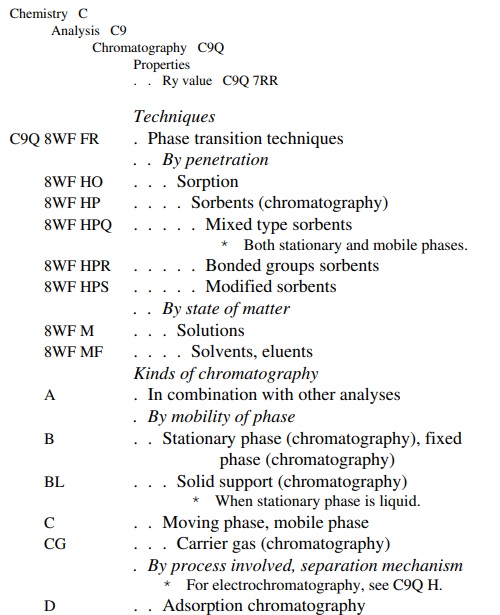

C9Q8WFFR – C9QD (section of chromatography)For publication purposes, the software is able to generate a visually structured display, calculating the hierarchy from the indent codes, such as 07), 08), etc., and identifying notes, node labels and so on, from the “non-class” symbol @. Other symbols are used to determine the typographic format, and to control entry (or otherwise) in the alphabetical index or thesaurus. In practice, this relatively simple markup is able to produce a high-quality print version of the scheme.

Figure 2: Camera-ready copy produced from sample source code shown in Figure 1

In 1987 the BCA was in discussion with a technology company, Computercraft, about the use of the BC software in conjunction with a thesaurus management system. This was in the context of the development of a thesaurus for the Royal Institute of International Affairs, based on the BC2 class R Politics and Administration. A letter dated June 1987 from Jean Aitchison, the consultant on the project, to James Cowan of Computercraft, describes previous work such as the use of the BNF STRIDE software to manage the DHSS-DATA Thesaurus, which was derived manually from the Bliss classification structure for health sciences. Aitchison says that the system “can handle the classmarks, but it cannot interact with the classification”, and describes various features that need to be incorporated to make the software more usable and more attractive to the market.

In 2004 the BCA’s own software was enhanced to include a thesaurus generation function (Broughton 2008), with very reasonable results, although it has not yet been used to produce a publicly accessible thesaurus. Most thesaurus features can be derived automatically from the original markup, such as the broader and narrower term relationships, and preferred and non-preferred terms, while associative terms still need to be determined manually. (For more detail see also below Section 10.)

In 2018/19 a project was put in place to create an XML version of the classification in the expectation that this would create a more accessible and editable form of the schedules. Consultant Richard Light has done some encouraging preliminary work, demonstrating that the BC2 structure and syntax can be expressed fairly readily in XML. Work is ongoing in this area examining various methods of converting both text and the coded format to an editable version; a prototype editor is being used for testing, but this is not yet publicly available.

4. Published volumes

Publication of the scheme began in 1977, and to date 15 volumes have been formally published, originally by Butterworths, then Bowker-Saur, Saur, and now de Gruyter.

Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules 1977 A/ALPhilosophy and Logic 1991 AM/AXMathematics, Probability, Statistics 1993 AY/BGeneral Science and Physics 2000 CChemistry 2012 HPhysical Anthropology, Human Biology, Health Sciences 1980 IPsychology and Psychiatry 1978 JEducation (3rd ed.) 1990 KSociety (includes Social Sciences, Sociology and Social Anthropology) 1984 PReligion, Occult, Morals and Ethics 1977 QSocial Welfare and Criminology (3rd ed.) 1994 RPolitics and Public Administration 1996 SLaw 1996 TEconomics and Management of Economic Enterprises 1987 WThe Arts 2007

Versions of most of these classes are available on the Bliss Classification Association website (www.blissclassification.org.uk); only Classes H, K, and T are not accessible in electronic format. Draft schedules are also available there for another twelve classes, mainly as PDFs, occasionally in Word format, or as scanned typescript. A number of published and unpublished classes also have links to the source code used to produce the PDFs and final copy.

2/9Generalia, Phenomena, Knowledge, Information Science and Technology D/DFAstronomy Word DG/DYEarth Sciences E/GQBiological sciences G/GYZoology scanned typescript GR/GZApplied Biological Sciences, Agriculture and Ecology scanned outline schedule L/OHistory (including Area Studies, Travel and Topography, and Biography) LAArchaeology U/VTechnology and Useful Arts (including Household Management and Services) scanned typescript WV/XMusic X/YLanguage and Literature ZA/ZWMuseology

5. Arrangements for maintenance

A major disadvantage of BC2 is that, as with its predecessor, there are no formal provisions for maintenance, and ongoing work is dependent on volunteer effort. A powerful argument for the radical nature of the revision was to mitigate the need for short term revision and updating, but fifty years from its inception there are obvious shortcomings in the scheme, not least that some parts remain unfinished. Work has been undertaken to make the scheme as freely accessible as possible in the hope that users, either of the scheme or of the terminologies, would contribute suggestions for updates and amendments, but to date there is little sign of this.

6. Principles underlying the classification

The classification is based on various theoretical and structural principles, some of which are inherited from BC1 and some of which are part of the more general theory of faceted classification. There is limited discussion of any philosophical or conceptual framework of facet analysis in the LIS literature, but Hjørland has proposed that the fundamental philosophical approach of facet analysis (and hence of BC2) is rationalist, that is, based entirely on logic and reasoning (Hjørland and Albrechtsen 1999, 134; Hjørland 2013; Hjørland and Barros 2024). Descriptions of the standard methodology of facet analysis would tend to support this idea, and certainly, the principles of classical logic are applied consistently in BC2 (Mills 2004). Conversely, some elements of the process (user consultation and mapping to the published literature of a field) can make a strong case for the role played by pragmatism (Dousa and Ibekwe-SanJuan 2014; Gnoli 2017). Interestingly, one of de Grolier’s observations in his unpublished review of BC2 (see Section 11) was that it was “in the English pragmatic tradition” (Mills 1991, 17), although we cannot be completely certain what he might have meant by that. A partial insight is given in his discussion of the CRG work in his 1960 study of general categories in which he states that the CRG classification schemes “are truly specialized, very “pragmatic” classification systems” (Grolier 1960, 99); by this he means the priority given to → user interest in deciding on the arrangement of such schemes, and the difficulty that approach creates for the construction of a general scheme. This aspect of pragmatism is demonstrated in the BC2 context by the use of “utility” or “purpose” in determining citation order, as described by Vickery and Mills (see below Section 7.2.1).

Two main characteristics of faceted classification schemes find their historical roots in philosophy (Mazzocchi and Gnoli 2010): the use of categorical analysis, which can be traced back to Aristotle (Moss 1964) or alternatively to Indian philosophy (Adhikary and Nandi 2003); and the use of level theory as an ordering tool for disciplines, subject fields, or phenomena, drawing on → Comte, Spencer, Needham and Feibleman (Gnoli 2008). Discussion of these philosophical roots does not feature in the BC2 literature, other than a fleeting reference in the Introduction 6.213.31 to Comte, who was a significant influence on Bliss particularly in respect of the “hierarchy of the sciences” (Shera 1965, 83) which principle drove Bliss’s original main class order, substantially retained in BC2. Otherwise, the effects of both categorical analysis and level theory in the BC2 context are explored in more detail below (Sections 6.2 and 7.1.1).

It must be acknowledged that the influence of the CRG on the creation of BC2 is a powerful one, and that many of the features of BC2 occur as a result of the CRG work on a proposed new general classification (Austin 1969; Foskett 1970). A complete discussion of the structure and theory of BC2 is provided in the Introduction to the scheme (Mills and Broughton 1977), to which readers are referred. A briefer description of the scheme is provided by Thomas (1992). A summary of the main features is given here.

6.1 Relationship with BC1

The reasons for revision, enumerated at Section 2.2 above, indicate some of the intended differences in the second edition. Provision needed to be made for developments in individual subjects, and for the emergence of new subjects, together with the introduction of the larger and more up-to-date vocabulary associated with these changes.

BC1 is widely acknowledged for the sound theoretical basis provided by Bliss, and which emerged from his detailed analysis of the organization of knowledge as evidenced in his writings. The general broad structure of the original classification is maintained, with some modifications as discussed below.

Differences within main classes are largely occasioned by the more rigorous application of facet analysis to their vocabulary, and the imposition of a strict citation order, which had in the original scheme been more tenuous in its nature. It is, however, often the case that the BC1 order reflects the order obtained through the process of facet analysis, and there is less disruption to the overall order of a class than might have been expected. In The Organization of Knowledge (1929, 154-50) Bliss seems to have anticipated something of the nature of faceted classification in his discussion of what he calls “cross-classification” or “duplex arrangements of vertical series, coordinate with regard to one principle or interest, crossed by horizontal series representing other aspects. […] This form of classification, graphically set forth, is often termed tabulation”. A more potentially complex arrangement also appears to be in his mind when he states:

A system of entities and relations may […] be surveyed from different aspects and traversed by diverse interests and purposes. There may accordingly be many classifications crossing or branching in many ways. A one-dimensional serial classification has no structural reach. […] Cross-classifications and two-dimensional graphs are also inadequate; for they become congested with ramifying details that would really require three dimensions for their structural representation, or even four dimensions.This, in conjunction with the broad principle of “general before special”, delivered a structure not dissimilar to that of a faceted class.

Bliss made various provisions for compounding, but the capacity for this in BC1 is much more limited than in BC2. BC1’s methods of compounding are through the use of auxiliary tables, both general, for commonly occurring concepts, and those special to a particular class, embedded in that class. Many of the special auxiliary tables are retained, albeit revised, in BC2; although they may appear redundant in terms of the general provision for compounding, in many cases they effect some economy in the length of classmarks. Bliss also included a general indicator for compounding between classes. An equivalent is available in BC2 for combination between main classes, in the form of the letter subdivisions of 9 in the Common Auxiliary Table for Form.

Many of the alternatives included in BC1 are retained in BC2, with the additional provision of alternative citation orders where the requirements of different user groups may vary. In the interests of standardization there is always a “preferred” treatment, usually reflecting standard citation order.

Bliss based his classification on three important principles: it should have an underlying theoretical classification of knowledge; it should reflect the way that users studied and applied knowledge (consensus); it should reflect the way that knowledge was published (→ literary warrant). Bliss is also generally credited with the introduction of three other important aspects of classification: gradation in speciality, hospitality, and flexibility. All of these are acknowledged in the revision, and some of Bliss’s principles are directly related to theoretical features of BC2. In his paper on the classification of a subject field, given to the Dorking Conference in 1957, Mills emphasised that the determination of the most significant aspects of a subject — the way in which it is studied, and the way in which it is practised and applied — correspond to Bliss’s ideas of educational and scientific consensus (Mills 1957, 34).

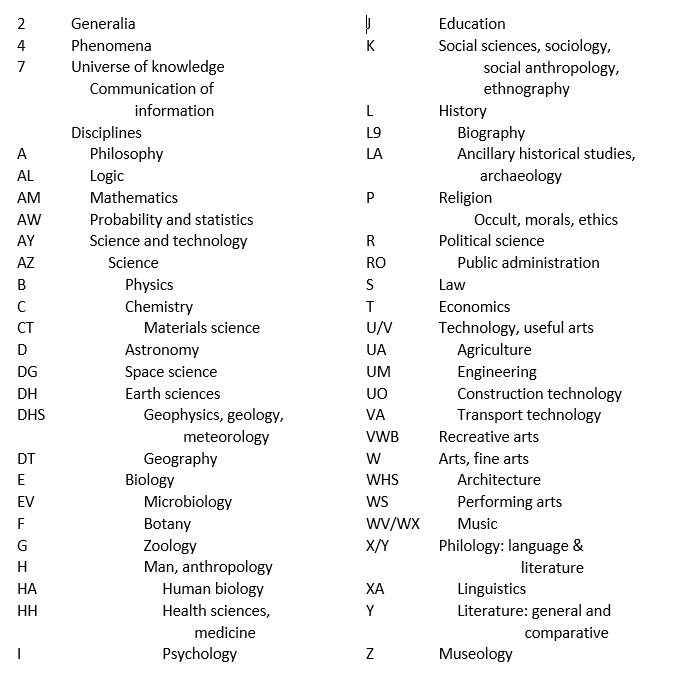

6.2 Main class order

A significant feature of BC1 was its excellent main class order, at which Bliss had laboured for so many years, and which is widely acknowledged to be the best of all the general classification schemes. Bliss attempted to achieve a perfectly modulated sequence of classes and gave much thought to the relationships between concepts in the various disciplines. His main classes also reflect that careful consideration of the modulation from one subject to another. This order of main classes is for the most part preserved in BC2, although the notational allocation varies somewhat to reflect modern perceptions of the relative documentary size of disciplines.

Bliss’s analysis of the universe of knowledge, and his consequent main class order, is largely derived from a part philosophical and part pragmatic consideration of individual disciplines and their structure. As Langridge says (1976, 5) Bliss’s premise is that “the order of the sciences is the order of things, and the order of things is the order of their complexity”. Classification theorists in the 1960s sought an intellectually more rigorous basis for this important aspect of classification design; in particular, the Classification Research Group, in their work on the viability of a new general classification scheme, examined various scientific theories for determining the relative order of subject domains.

The theory of → integrative levels, in the form proposed by Needham (1937), and Feibleman (1954), was seen as providing a legitimate theoretical foundation for a linear sequence (Foskett 1961; 1978; 1991), and the order in BC1 was observed to approximate very closely to this. The most general levels of matter, life, mind and society correspond neatly to Bliss’s groupings of physical, biological, human and social sciences, and Bliss’s principle of gradation by speciality is consistent with the general tenets of integrative level theory. A developmental order is also evident in BC, moving generally from the abstract to the concrete (implicitly reflecting → Ranganathan’s organizing principle), and which exhibits increasing complexity in the different disciplines, and the principle of dependence of each on preceding disciplines. This is articulated in The Organization of Knowledge and the System of the Sciences (Bliss 1929, 300):

Intelligence accepts the truth that in all probability there is some real transition from sphere to sphere, from the physical to the vital and from the vital to the mental, as there plainly is from the natural to the human and from the individual to the social, and as we may rationally believe there is from the human to the divine and universal.

Spiteri (1995) provides a useful introduction in her analysis of the Classification Research Group’s discussions of integrative level theory as an organizing principle in classification.

6.3 Modifications of main class order: classes, disciplines, and phenomena

The Introduction to BC2 makes careful distinctions between the three concepts: class, → discipline, and phenomenon. It concedes (1977, 5.54) that: “the term “main class” is an ill-defined one and there is some confusion between it and the idea of discipline”. At 5.542, “a further confusion results from use of the term “disciplines” in referring to what are essentially sub-disciplines”. In BC2, what Bliss would have considered as a discipline (physics, chemistry, biology, and so on) are regarded as sub-disciplines, that is the subdivision of a fundamental discipline, such as science, by particular phenomena (energy, matter, living creatures).

The main class order of BC2 was influenced to an extent by this notion of fundamental disciplines as proposed by Langridge (1976). It claims that there exists a small number of different disciplinary methodological approaches as distinct from the more numerous fields of study in the traditional understanding of disciplines as concerned with specific phenomena. These approaches include philosophy, history, → science, and religion, each with its own particular underlying conceptual framework, theory, and methodologies. These should form the main structure of a classification, with each discipline then subdivided by phenomena. This viewpoint is formally acknowledged in the Introduction to BC2 (1977, 5.53): “[a] stricter and probably more accurate way of regarding disciplines is to see them as reflecting different ’forms of knowledge’, or ways of looking at the phenomena of the world. The concepts and methods of enquiry of the scientist, the philosopher, the historian, the artist and so on are very different, although the phenomena they consider may be to some extent the same”.

Langridge is sceptical about the scientific approach to knowledge organization on the basis that it is only one view of the universe of knowledge, and not necessarily a legitimate one, with its assumptions that there is an objective external world, and that the scientific paradigm is the means to express it; this view is, of course, at odds with Bliss’s conception of the natural order of things. Otherwise, a division along these disciplinary lines is not greatly at variance with the BC order, except insofar as it has been proposed to move class P, Religion, to the end of the sequence (class Z) on the basis that books in the realm of religion have a different conceptual perspective to those in the realm of, for example, science.

The current editor’s view is that this approach to religion is not useful from a bibliographic perspective. A distinction needs to be made between books about religion (which constitute the majority of items in a religion collection and are generally scientific in nature) and books of religion (which may well have a different world view). A case might be made for the separation of religious books, but it would cut across the traditional disciplines (e.g., religious treatments of evolution, or monetary lending, or abortion) and create a new set of ordering problems. The conventional classification solution using a common subdivision (“history of”, “philosophy of”) accommodates such material satisfactorily without making the fundamental discipline the principal means of arrangement.

Some allowance ought also to be made for Bliss’s distinctive treatment of religion in BC1, placing it among the social sciences where it is an example of a sphere of activity in human society, alongside law, economics, politics and so on. This view conforms more readily to the modern academic discipline of “religious studies”, dating from about the 1960s, in contrast to traditional “theology” where a lens of religious belief, commonly of one persuasion only, is applied to scholarship.

6.4 Phenomena

A distinctive feature of BC2 as compared to BC1 is provision for the treatment of entities, or → phenomena, as separate from their usual disciplinary, or sub-disciplinary, context. Acknowledging that phenomena are essentially scattered in the general classification scheme with its initial division into disciplines, BC2 (1977, 5.552) asserts that “it should be recognised that there is, theoretically, a quite different way of organising a general classification. This would be to make the first division of the field of knowledge into phenomena (from subatomic particles to planetary bodies and stars, from single cells to particular organisms and particular societies, and so on) and to subordinate to each phenomenon the disciplinary aspects from which it may be treated”. Such an alternative approach to classification is accommodated using the anterior numeral classes 4/9.

The Introduction goes on to state (1977, 5.553) that “[s]uch an arrangement would run counter to the way we usually study things and the way most information is marketed, which reflects the division of labour by discipline. There are relatively few persons, if any, specialising in a given phenomenon from all its aspects. Indeed, such a specialised study would require a training which is at present hard to envisage”. Forty years later this is increasingly not the case with, for example, many higher education programmes focusing on a phenomenon rather than disciplinary conventions; women’s studies, in its infancy in 1977, is the classic example, but in the UK degrees as diverse as mediaeval studies, early childhood studies, Celtic studies, addiction studies, Islamic studies and refugee studies, proliferate. Beghtol (1998, 6) in an evaluation of different schemes’ treatment of multidisciplinarity, confirms this, saying that the “growth rate of multidisciplinarity is now remarkably fast, and BC2 appears to offer more complete treatment of these works than the other systems discussed”. Interestingly, Gnoli (2005, 20), writing a little later, in a critique of the phenomena classes in BC2, observes that “focusing on phenomena […] is not very fashionable in present-day classification research: one can find it in past decades in work by CRG members and by Dahlberg, while today people appear to be more concerned with relativistic issues such as locality, cultural biases, social use of information, etc.”

In 1977 it was possible to state (1977, 6.214.1) that “the phenomena in the BC constitute a new feature, which has not been attempted before in a general classification, although studies undertaken for the Classification Research Group in London looked closely at the problems involved” (Austin 1969). In fact, in 1906 → James Duff Brown had attempted something comparable in his Subject Classification where the categorical tables are used to represent aspects of a subject, and the list of subjects has some bizarre collocations such as the inclusion in Physics of church bells (under Sound) and fire engines and chimneys (under Heat).

To date there is very little in the way of developed BC2 schedules for phenomena, and only three classes are allocated in the outline provided in the Introduction (1977, 202).

(Phenomena)

* For multidisciplinary treatment of particular phenomena

* Alternative (preferred) is to collocate with most appropriate disciplinary treatment, applying the principle of unique definition (mainly for phenomena appearing in the natural sciences and purpose (mainly for phenomena in social science and humanities)4Attributes (e.g. structure, order, symmetry, colour) 5Activities and processes (e.g. organizing, planning, change, adaptation) 6Entities (e.g. particles, atoms, molecules, minerals, organisms, communities, institutions, artefacts)

This outline of the phenomena classes goes on to list the “universe of knowledge” and communication and information. It should be observed that the notational allocation here is compromised by the later development of a draft schedule (www.blissclassification.org.uk/Class2-9/2-9_sched.pdf) where the phenomena proper are limited to class 3.

It is clear that it was never the intention to adopt a totally phenomenon based approach in BC2, which aims only to provide a location for documents where concepts are treated from a multi- or non-disciplinary perspective; the three possible means of doing this (1977, 6.221) all envisage at least some documents being allocated to the discipline based classes. While the question of whether provision should be made for “a classification of all or some phenomena in which the phenomenon was cited before the discipline” is touched on (1977, 6.214.56), it is dealt with rather summarily, as it “seems clear that BC would be inconsistent in view of its general policy not to provide such an alternative so it will in fact provide one”.

The Introduction includes a lengthy discussion (1977, 6.214.5) of the difficulties associated with classifying phenomena in a scheme which would still be predominantly discipline based. These include the process of extracting the phenomena from lists in main classes, and the associated problem of deciding on a preferred order of concepts where those concepts occur in more than one disciplinary class and are differently ordered there (animals in zoology and animal husbandry are an obvious example). (Although it is not raised here, there is an associated difficulty with the use of multiple notations for the same concept in different disciplines: Gnoli 2005, 17) Interestingly, Riggs (1987, 42) in his review of class K, Society, comments on the choice of main class name, which suggests that the focus is on the phenomenon of society, rather than the discipline of sociology. This is mirrored in other revised classes, for example, Religion rather than Theology, but it not carried through consistently.

There is also the matter of an alternative provision for multidisciplinary works where a library does not wish to use the phenomena classes. Here, multidisciplinarity is treated as a kind of common subdivision, and filed immediately after the main (disciplinary) class heading (1977, 6.214.55):

It is proposed, therefore, to file the multi-disciplinary treatments immediately after the disciplinary ones, using the numeral -1 to notate it exactly (the common subdivisions in Schedule 1 begin with the number -2):

GYH JHorse (Zoological studies, general)GYH J1Horse (multi-disciplinary studies)GYH J2HHorse (Zoological studies) – Pictorial material

This solution is achieved through the notion of the “place of unique definition” originally proposed by Farradane (1950, 87), which rules that “for any given concept, the minimum information needed to define it is to be taken as the clue to its location” (1977, 6.214.61) or alternatively, “that class which provides a given concept with its most fundamental defining characteristics, e.g. Zoology provides the place of unique definition for the concept Horse” (1977, 107). It should be acknowledged that Farradane’s system of relational indexing did adopt a non-disciplinary approach, with the objective that concepts, or isolates, as Farradane called them, were context free and must have only a single location. The problems of ordering concepts in an entity-based classification were explored by the CRG, and in particular by Austin (Austin 1969, 156-7; 1976). Reference here should also be made to the → Integrative Levels Classification (ILC), devised by Gnoli and others, which follows a similar line, and makes phenomena the primary approach to the whole system (Gnoli 2011; Szostak 2007). A significant factor here is the emergence, and increasing importance of interdisciplinarity in academic research, which feature was not a consideration in the initial stages of the BC2 revision.

7. The structure of BC2

The Introduction and Auxiliary Schedules (1977, 38) asserts that:

A bibliographic classification consists of:

5.621 A vocabulary of terms organised into broad facets; 5.622 Within each facet, terms organised into sub-facets, or arrays; 5.623 A citation order for the formation of all compound classes (i.e., classes of more than one term reflecting the intersection of concepts from different facets or from different arrays within the same facet); 5.624 A filing order for the resulting classes (simple and compound); 5.625 A notation to maintain the filing order; 5.626 An alphabetical index of terms to locate them in the classification.

This broadly corresponds to the chronological sequence followed in constructing the classification, beginning with the organization of the vocabulary into facets.

7.1 Facet analysis in BC2

Vickery (1960, 12) states that the “essence of facet analysis is the sorting of terms in a given field of knowledge into homogeneous, mutually exclusive facets, each derived from single characteristic of division”.

Its faceted structure is certainly the most distinctive feature of BC2, and the one that usually distinguishes it from other western schemes of classification in general use. Alongside the Colon Classification, it is a general scheme constructed ab initio by facet analysis. Most schemes now exhibit some elements of faceting, and the UDC is in a process of gradual conversion to a fully faceted form, but still has many examples of enumeration in its schedules. An exception should be made for the Integrative Levels Classification, but this is intended primarily as a source of metadata for post-coordinate indexing of research material rather than a general organizational tool applicable to physical document collections.

Ranganathan is generally credited with devising the method of facet analysis, although examples of similar analytical approaches to knowledge organization can readily be found in earlier systems, in the UDC, Brown’s Subject Classification (1906), and most noticeably in the work of Kaiser (1911), who identifies categories such as place, process, and concrete in document content (Dousa 2013). There is also evidence that facet analysis emerged independently in other disciplines, particularly in the social sciences (Beghtol 1995). The approach adopted in BC2 is rooted firmly in the Ranganathan tradition but is tempered by the modifications of that tradition made by the UK Classification Research Group throughout the latter part of the Twentieth century, and which employs thirteen fundamental categories as opposed to Ranganathan’s five. It may be useful here to make the distinction between category and facet.

7.1.1 Fundamental categories

Ranganathan understood a category to be “a form or class of concepts, varying from subject to subject, into which isolates can be grouped”, and a facet to be “the subclasses of a basic class corresponding to a single fundamental category” (Campbell 1957, 13). The glossary in BC2 does not define category (and tends to employ facet for preference) but it may be broadly understood as an abstract and generic concept, one which may be employed in any domain for the purpose of analysing and grouping the vocabulary. Terms or concepts are assigned to categories on the basis of their functional (or sometimes linguistic) nature, and in this they have something in common with role indicators in indexing. Ranganathan’s categories of personality, matter, energy, space and time were considered by the CRG to be limited, and they discerned a larger number. Vickery (1960) suggests a list of thirteen: substance (product); organ; constituent; structure; shape; property; object of action (patient, raw material); action; operation; process; agent; space; and time. BC2 uses a variant, and slightly reduced, version of this set, in naming nine major categories:

end product (often called thing or entity); its types; its parts; its materials; its properties; its processes; operations on it; agents of action; place; time.

In practice this list is itself subject to amendment as the needs of different domains determine, and categories such as patient and by-product are also to be found, as are some humanities and arts related categories, such as genre and form. In 1993 a new fundamental category, that of relation, was used in the analysis of the Mathematics class. It was used to accommodate concepts such as functions, equations, homomorphisms, and so on, and lies conceptually somewhere between processes and properties. There is a body of research around the nature of fundamental categories, and their range and number. Much of the groundwork here is in the faceted classifications developed in the mid-Twentieth century, and which are discussed in some detail in de Grolier’s book A Study of General Categories Applicable to Classification and Coding in Documentation (Grolier 1962).

7.1.2 Facets proper

The notion of a → facet is very variously understood (Hudon 2020), often being limited to an aspect, or a property of some entity or activity, and that is the way it is commonly considered in web information work (La Barre 2006). In other situations, facets may be equated with, for example, the fields in a bibliographic record, such as author or date of publication (Broughton 2023, 427). In the BC2 context a facet is quite explicitly one conceptual dimension of a subject field.

When a given category is used to accommodate concepts in a particular subject field or domain, the result is a facet. In BC2 (1977, 38) “[a] facet may be defined as the total set of subclasses produced when a class is divided by a single broad principle”. This dividing principle is the fundamental category, so that, for example, the application of part to the vocabulary of medicine will generate the facet of “parts, organs and systems”, or the application of entity to chemistry results in the facet of “substances”.

This can be seen within the context of a particular main class, for example:

Medicine

Entity, end-product (persons, human beings)

Parts (anatomy, parts, organs and systems of the body)

Processes (physiology, diseases and pathology)

Operations (treatment, preventive medicine, curative medicine, clinical medicine, therapy)

Agents (medical materials, drugs, technology, medical personnel, organizations)

Place

Time

7.1.3 Order of classes within facets

There is no particular theory that determines the sequence of classes within a facet, and various pragmatic and common-sense solutions are normally adopted, such as order of size, order of development, spatial contiguity, and so on. Ranganathan’s “canon of helpful sequence” (Ranganathan 1967, 183) provides eight principles for such order: later-in-time, later-in-evolution, spatial contiguity, quantitative measure, increasing complexity, canonical sequence, literary warrant, and alphabetical sequence. Vickery (1959, 30) suggests nine possible principles, based on Richardson (1930): logical, geometrical, chronological, genetic, historical, evolutionary, dynamic, alphabetical, and mathematical. For example, in the field of reproductive medicine the developmental sequence “zygote – embryo – foetus” is observed for in utero structures. In some cases there is no particular natural sequence, and the order is arbitrary; for instance, in parts, organs and systems of the body, a head-to-foot order of arrangement is imposed, both for the organs themselves, and within pervasive systems such as bones and nerves.

7.1.4 Relationships within facets

Since all the concepts within a facet are of the same categorical status i.e., all properties, or all processes, the relationships between concepts are necessarily restricted to those of hierarchy, superordination and subordination. Hierarchical relations are shown in the linear order by indentation within each facet (1977, 6.343), and because the BC2 notation (see below) is not expressive of hierarchy this symbolism is strictly observed throughout. For example, in (the draft schedule for) Music:

WWS WWIND INSTRUMENTS ZWoodwinds WWTFlute WWT WPiccolo WWT XRecorder XSDescant XTTreble XVTenor XWBass WWU BOboe COboe d'amore DCor anglais KClarinet (B flat) LClarinet in A MBass clarinet NBassett horn OBassoon

Every indentation implies that the indented class is, in some way, a subclass of the one immediately above it. However, the relation of a subclass to its containing class does not always reflect the conventional relationship of a species to its genus (1977, 7.391.3); for example, the whole/part or system/sub-system relationship is also common.

7.1.5 Arrays (subfacets)

The number of concepts or classes in a facet may be very considerable; the number of substances in chemistry, for example, runs into many millions. It is therefore necessary to provide some further organizing principle within the facet. The result of such subdivision is known as an array (sometimes referred to as a subfacet), and the means by which it is created is called the principle of → division, or characteristic of division (in the vocabulary world this is usually referred to as a node label). A facet of persons, for example, may be divided by principles of division such as “persons by age”, “persons by social class”, “persons by religion”, and so on, to give arrays of the kind:

Persons Persons (by age) (by religion) Infants Atheists Children Hindus Adolescents Jews Adults Muslims Young adults Pagans Middle aged persons Sikhs Older persons

An important idea in the construction of arrays is that of mutual exclusivity, which is frequently misunderstood. It states that the concepts within an array must be mutually exclusive and means that (in the examples above) a person cannot be both a child and a middle-aged person, a Jew and a Sikh. If this is not the case, then the array is not properly constructed and should be re-examined. It is also important that the principle of division is exhausted, that is to say that all its possible values are represented. Mutual exclusivity does not mean that the arrays are mutually exclusive, or that concepts from different arrays cannot be combined to give, for example, Hindu children, or older Muslims. Similarly, the complex subjects found in documents may involve more than one concept from the same array (for example, “music education for children and adolescents” or “interfaith activities of Christians and Muslims”).

The same observations about the order of concepts discussed under facets also apply to arrays.

7.1.6 Relationship between facets: combination of concepts

The second most important feature of the faceted classification, after its logical structure, is the facility to combine concepts to express any complex subject content of documents. In BC2, in principle, any number of concepts can be combined, but this must be done in conformity with various rules. The central rule of combination is that of citation order. Citation order also determines the sequence of facets in the linear order within the classification, using the principle of inversion (see Section 7.3).

7.2 Citation order

Citation order, in earlier times often referred to as “combination order” (Vickery 1959, 88; 1968, 57), is “the order in which the elements of a compound class are cited when we state the class as a string of terms” (1977, 5.731). Hence, a compound subject described as a string of concepts might be:

Primary school children – reading – phonicsin conformity with the citation order:

Type of person taught (educand) – subject taught – teaching method

Citation order can be seen in any classification where combination in supported, and in compound subject headings, such as LCSH. The application of rules comparable to citation order can also be observed in the display of any physical collection of items, such as objects in a museum, or foods in a supermarket.

The first cited element will naturally determine where in the physical collection a document is located, and the use of an appropriate citation order is particularly important in the physical document collection since it determines the overall sequence of classes in a subject field and which aspects of a subject are distributed or scattered. In the example above, for instance, material on a particular type of educand is kept together, but material on the subjects taught, or the techniques used, will be scattered. The use of a consistent citation order is also vital since it allows the user to predict where material about a compound subject will be located and enables the retrieval of aspects which are distributed.

7.2.1 Citation order between facets

The order in which terms from different facets should be combined is mainly determined by established faceted classification theory. Ranganathan was the first to formulate this, stating that order of combination of categories should be according to his famous PMEST formula: Personality – matter – energy – space – time. This follows the rule of decreasing concreteness i.e., that the most specific categories are cited first, working down to the most abstract. This generates a sequence which is intuitive for most library users, with the most concrete, or specific, concepts kept together (for example, animals in zoology) and the more abstract elements scattered.

Vickery (1959, 32) states that the idea of what he calls “utility” “is far more helpful than that of concreteness” in determining the primary facet. This concept he credits to Mills (1957, 34) who describes it as reflecting “the purpose of the classification” and that “material should be collected on that aspect of the subject which is most important to the user”. It is otherwise identified as the end-product, or the purpose of the subject (Mills 2004, 557). This principle is generally employed in BC2 alongside the combination order established by the CRG. The CRG combination order is an elaboration of Ranganathan’s categories, namely:

Thing – kind – part – material – property – process – operation – agent – space – time

This observes the Ranganathan rule of decreasing concreteness, but also employs the idea of dependence (closely related to that of the end purpose); e.g., an operation must be performed on some entity, and the agent of an operation must have an action to be agent of. So, in a subject stated as the chain of terms:

Hospitals – Wards – Floors – Finishesthe Finishes “serve” the Floors, which “serve” the Wards, which “serve” the Hospital, which serve the purpose of housing the sick. This also reflects to some extent the thinking behind integrative level theory, where each level “serves”, or is dependent on the existence of the one below, e.g., fundamental particles are dependent on the existence of forms of energy, the chemical elements are dependent on fundamental particles, compounds are dependent on the elements, minerals and rocks are dependent on compounds, geographical features are dependent on minerals and rocks, and so on.

The CRG order is commonly referred to as standard citation order, which term is generally accredited to Vickery (1960). This order is used as the default order throughout BC2, although there are some local variations according to the needs of the subject.

7.2.2 Citation order between arrays

As well as combining concepts from different facets, it is also necessary to combine concepts from different arrays in the same facet (as in the examples given above). There is no general principle for this analogous to those for facet citation order (1977, 5.735.1), since the idea of dependence is not relevant. However, there are some individual principles which can be applied. The general principle of purpose (used to determine the primary facet) can often help in deciding on priority, as in the example of “High rise flats” where the function of the building (flats) is cited before simple, or more general properties (high rise), i.e. “Flats – high rise”.

Because there is no comprehensive theoretical principle yet developed, it would seem accurate to say that on the whole deciding citation order in array is largely a pragmatic business (1977, 5.735.5).

7.3 Filing order

Filing order is the linear order, or sequence, of classes in the classification scheme. Filing order in BC2 is controlled by three main principles: general-before-special, gradation in speciality, and increasing concreteness. Filing order is also reflective of general philosophical notions, such as those employed to determine the order of phenomena and of main classes (Section 6.2 above), and it also demonstrates relationships between classes such as super- and subordination.

General-before-special requires that a class which completely contains another class files before it. Thus, the class of “animals” precedes that of “mammals” and “mammals” precedes “horses”, “dancing” precedes “ballroom dancing”, and “crime” precedes “murder”. Such an order appears to be intuitive for users.

Gradation in speciality is a more complex notion and related to the concept of integrative levels (see Section 6.2). It requires that a subject which is dependent to a degree on another subject should file after it. For example, “biology” makes use of chemical laws and concepts to explain some of its data, although the reverse is not the case. Therefore “chemistry” precedes “biology” in the sequence.

Increasing concreteness is a rule which is implicit in the schedules. It states that classes in the linear sequence should proceed from abstract to concrete; so abstract topics such as “philosophy” or “theory” come before concrete concepts such as “diesel engines” or “bungalows”. The principle of increasing concreteness is particularly important in determining the filing order of facets.

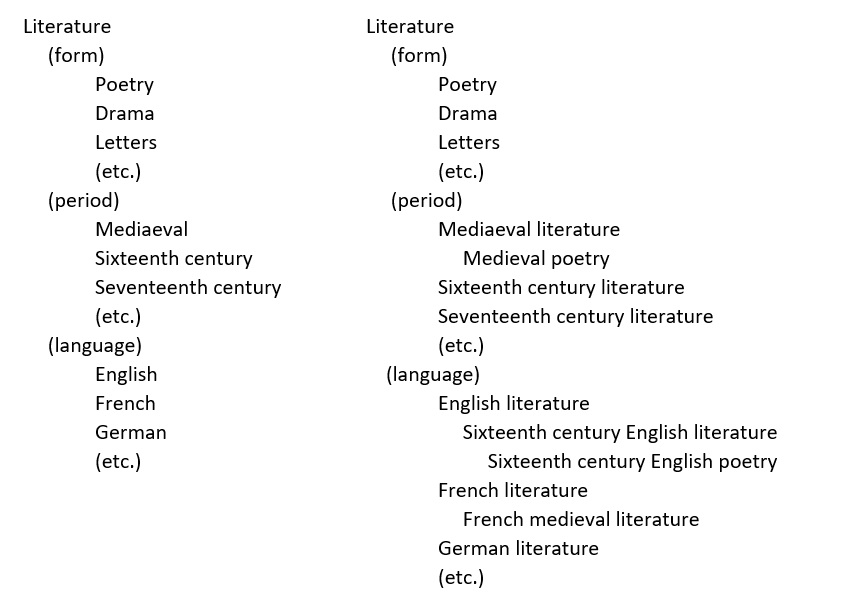

7.3.1 Filing order of facets

Applying the principle of increasing concreteness to the facet filing order, facets are filed in the reverse of citation order. That is, the last cited facet (usually time) files first in the schedule, followed by the penultimate facet (usually space), and so on, with the primary facet (personality, entity, etc.) filing last; the sequence thus moves from the most abstract to the most concrete. The resulting schedule is said to be inverted.

For example, in the class Literature the first cited facet would be Language, the second cited would be Period, the third literary Form, and so on. If we file these in the order of citation the resulting schedule looks like this:

Literature

(language)

English

French

German

(etc.)

(period)

Mediaeval

Sixteenth century

Seventeenth century

(etc.)

(form)

Poetry

Drama

Letters

(etc.)

However, when concepts are compounded to represent the subjects of documents, the following (example) filing sequence would result:

Literature

English literature

Sixteenth century English literature

Sixteenth century English poetry

French literature

French medieval literature

Mediaeval literature

Poetry

English poetry

This breaks the rule of general-before-special, with, for example, French mediaeval literature preceding Mediaeval literature, and sixteenth century English poetry preceding English poetry. Such a sequence would be illogical, and unhelpful and confusing for readers. If, however, the filing order of facets is reversed, or inverted, a much more satisfactory order is achieved. This does not conflict with any of the filing principles and creates a more intuitive collocation of topics.

7.4 Notation

The → notation in BC2 uses both capital letters of the Roman alphabet and Arabic numerals. Numerals have a lower filing value than letters and precede them in the sequence. Other symbols such as punctuation marks or non-Roman letters are not used. At the top level of the classification, numerals are used for the Generalia classes including phenomena, and letters for main classes. Otherwise, broadly speaking, letter classmarks predominate, and numerals are used to indicate subsidiary and common classes. In the classification display a space is inserted after three characters, but this is simply for ease of reading; it has no semantic significance and can be omitted in labelling documents or records.

The primary function of the notation is to maintain the filing sequence and the order of classes as they have been determined by the methodological principles of BC2. A significant feature of the BC2 notation is that it is non-expressive either of hierarchy or of the structure of built classmarks. One of Bliss’s objectives was to provide short, economical classmarks, and this policy has been followed through in BC2. This has the advantage that overall, the classmarks are short, and therefore more easily understood and remembered by users; additionally, since the classmarks are not required to express anything of the semantic nature of the classes, short classmarks may be allocated to important subjects, that is, those with a substantial volume of literature. The lack of expressivity of the notation can be counted a disadvantage, particularly in the digital age, since the classmarks cannot be readily interpreted by software. The classmarks are not suitable as a basis for machine retrieval since the notational coding for any concept is not necessarily consistent, and it may not be recognised within a built classmark. This has been a problem in the development of the digital version of BC2 where the natural affinity of the faceted scheme with complex search and navigation is compromised by the non-expressive notational coding. The problem is alleviated to some extent by the use of hierarchy codes in the local BC2 markup.

7.4.1 Retroactive notation

The notation is fully faceted and synthetic and is used to support the synthesis or building of classmarks to represent compound subjects. Because of the principle of inversion, in order to apply the citation order, the concepts in a compound are combined in the reverse order of that in which they appear in the schedule (retroactive synthesis). The notation is allocated in such a way that in each facet notational space is left to allow for the addition to any class of all preceding facets. For example, in class J:

JEducation JAPrinciples of education JBEducational administration JKCurriculum JLSchools by characteristics other than stage of education JMPrimary schools JMNPreparatory schools

The first enumerated subclass of JM Primary schools JMN Preparatory schools is assigned a letter (-N) later in filing value than those introducing preceding classes (-A for Principles of education, -B for Administration... -L for Curriculum) so compounds can be formed by direct addition of these to JM (e.g., JMK Primary school curriculum) without clashing with the enumerated subclasses.

7.4.2 Intercalators

If this principle were strictly followed throughout the scheme, then number building would be a very straightforward matter, since the notation for each concept in a string need only be combined in the reverse of alphabetical order. In practice, because of the pressure on the notational allocation, it is not possible to sustain a pure retroactive method, and building is sometimes supported by the use of intercalators (a notational symbol which allows the insertion at a required point of one or more qualifying facets). In BC the letter A is often used to replace retroactive synthesis, when the reservation of a large number of letters to accommodate preceding facets and arrays proves inconvenient. For example:

QFSocial security QFA* Add to QFAlettersA/EfollowingQinQA/QE

e.g.QFCSocial security in UK or favoured country

While this device has maintained the policy of shorter classmarks, in practice it is found confusing by classifiers, and no doubt reinforces the belief that BC2 is complicated to apply.

7.4.3 Notational replication and specifiers

It is often the case that concepts in one part of a schedule have relevance in another, and since the essence of a faceted scheme is that it should not unnecessarily enumerate, or duplicate, classes, terms from one facet or array are “borrowed” to generate classes in another. A typical (and frequent) example is where geographic terms are used to create national or cultural concepts in a different part of the schedule, but many other examples occur. For instance, in Architecture, terms from the facet of building materials are used to create the classes “Buildings by material” e.g., Timber as a building material WHO MT, Timber buildings WHT VMT. Such a term (i.e. timber) is defined as a specifier, that is, a term which defines a species of something by a characteristic occurring elsewhere in a different relationship. The significance here is in the different relationship; timber as a material is not the same as a building made of timber (nor is Japanese music the same as Music in Japan).

7.5 Pre-combination within the schedules

A particular feature of BC2 particularly in its later volumes, is the provision of pre-combined or pre-coordinated classes for many compound subjects. This practice has two objectives: firstly, to provide guidance in the business of synthesising classmarks; and secondly to ensure that concepts that are semantically compound but terminologically “simple”, are represented in the schedule (and therefore in the index) and are consequently discoverable. For example, the concept “Arthritis” is a compound one represented by adding the notations for “joints” and “inflammation”. While there is no theoretical reason why the classifier should not construct this for her/himself, it greatly reduces the work of classifying documents if these pre-coordinated classmarks are provided, especially in a field like medicine where technical terminology proliferates. The logical outcome of this feature is that it greatly enlarges the schedules, but it accommodates a much greater range of vocabulary, and it allows for the construction of a much more sophisticated and complex classification than would be the case for a bare facet structure.

7.6 The alphabetical index

An alphabetical index is provided in each published class, although there is no integrated index to the whole scheme. The index has two main functions: to indicate the locations (and therefore classmarks) of subjects; and to bring together distributed examples of those subjects i.e. to show where a subject occurs in different contexts. For example, in class C Chemistry:

Reactivation

: AnalysisC9Q 7QL

: Organic chemistryCUL BSG

: Physical chemistryCBS G